“…Facing the most remarkable bay in the world, the architect has designed this factory to respect its beautiful surroundings and to make this beauty a source of comfort in the working day. We wanted nature to be part of the life of the factory rather than being excluded by a building which was too large, in which the windowless walls, air conditioning, and artificial light would diminish, day by day, the spirit of those working there.

The factory was therefore designed to a human scale because in such surroundings the workplace will be an instrument of fulfilment and not a source of suffering. So we wanted low windows, open courtyards, and trees in the garden to banish the feeling of being in a constricted and hostile enclosure….”

60 years ago, on the 23rd April 1955, with these words in a speech to his employees, Adriano Olivetti opened his new office machine factory in Pozzuoli overlooking the Bay of Naples. These are not the sort of words usually uttered by a factory owner but Olivetti was no ordinary boss. One of the most remarkable industrialists and intellectuals of the Twentieth Century he had developed a utopian vision of the place of industry in society that this pioneering factory exemplified. This vision had developed in the twenty years since he took over the direction of his father’s company in 1933.

BACKGROUND

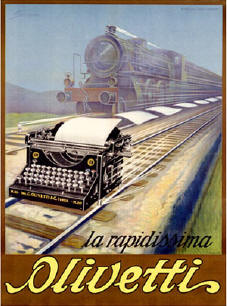

In 1908 Camillo Olivetti (1868-1943) had established Ing. C. Olivetti & C. in the small northern Italian town of Ivrea, near to Turin, as Italy’s first typewriter factory (illus.). A gifted engineer, he had been inspired by a stay in the USA to first import, then make, typewriters which were becoming essential equipment in most offices. The company grew rapidly and by the early 1920s was employing 250 and making over 2,000 machines a year. Olivetti was also an early Socialist, involved in radical politics at the turn of the century, and he published two left-wing newspapers. His factory pioneered social reforms in a country with generally appalling working conditions providing his employees with health and accident insurance, good wages, apprenticeships, further education, and subsidised housing. His socialist and anti-fascist views soon brought him, and his son Adriano, into conflict with the Mussolini regime and it was only the state’s need for Italian-made typewriters (as vital as computers are today) that prevented the firm from being closed down during the Fascist period.

In 1908 Camillo Olivetti (1868-1943) had established Ing. C. Olivetti & C. in the small northern Italian town of Ivrea, near to Turin, as Italy’s first typewriter factory (illus.). A gifted engineer, he had been inspired by a stay in the USA to first import, then make, typewriters which were becoming essential equipment in most offices. The company grew rapidly and by the early 1920s was employing 250 and making over 2,000 machines a year. Olivetti was also an early Socialist, involved in radical politics at the turn of the century, and he published two left-wing newspapers. His factory pioneered social reforms in a country with generally appalling working conditions providing his employees with health and accident insurance, good wages, apprenticeships, further education, and subsidised housing. His socialist and anti-fascist views soon brought him, and his son Adriano, into conflict with the Mussolini regime and it was only the state’s need for Italian-made typewriters (as vital as computers are today) that prevented the firm from being closed down during the Fascist period.

Adriano Olivetti (1901-1960) shared his parents’ socialist opinions and strong moral purpose and, although trained as an engineer, he became an editor of one of Camillo’s newspapers at an early age. However, the failure of Italian socialism in the early 1920s and the rise of Mussolini disillusioned him (1) and he decided against a career in political journalism, joining the family firm as an apprentice in 1924. Following a tour of America in 1925, where he saw the mass-production methods of Ford and the vast Remington typewriter factories, he persuaded his father to transform the rather old-fashioned way Olivetti produced its machines. By the time Adriano became president of the firm in 1938 it had grown by 400% into a global business employing more than 2,000 workers.

During this period of rapid expansion the welfare of the Olivetti employees had not been forgotten. Adriano’s enthusiasm for modern management techniques included the development of social policies along with a new emphasis on industrial and graphic design, and modern architecture. Increasing profits were used for the benefit of the company’s workers. A foundation was created to provide financial assistance to injured or sick employees, social services were extended to include a health service, convalescent home, libraries, schools and a summer camp, and a whole district of subsidised worker housing was planned. Olivetti had embraced Modernism with enthusiasm, inviting Le Corbusier to Ivrea in 1934 to discuss management, architecture and planning. He brought together a group of young avant-garde Milanese architects to help him plan the expansion of the company’s facilities, and to develop a regional plan for the area around Ivrea which culminated in the Piano Regolatore di Valle d’Aosta (General Plan of the Aosta Valley) in 1937.

1936 Factory extension, Ivrea, Architects Figini and Pollini (1949 extension by the same architects in the background)

1936 Factory extension, Ivrea, Architects Figini and Pollini (1949 extension by the same architects in the background)

The Olivettis’ relationship with the Fascist regime had been complex. Rather like Leitz (Leica) in Nazi Germany, the family’s politics and opposition were well known but the state needed their expertise and products. Their newspaper (Tempi Nuovi) was forced to close in 1925 after being attacked by the Fascists, and Adriano had a brief period of exile in London following his involvement in the escape to France of Filippo Turati, the veteran Socialist leader, in 1926. Despite this, to protect his business, he joined the Fascist Party in the late 30s whilst continuing his clandestine support for the anti-fascist movement. After the Nazi occupation of Italy he had to escape again in February 1944, this time to Switzerland, after being imprisoned by the Badoglio government. His father had already gone into hiding to avoid arrest, and he had died in December 1943. The Olivetti factories in Ivrea became the headquarters for the partisans in the region, and 24 employees were killed during the resistance struggle.

COMUNITA’

Olivetti had started to think about the reconstruction and ‘resurrection’ of post-war Italy as early as 1942, and his exile in Switzerland provided an opportunity for him to develop further his theories on urban and regional planning that he had begun with the Valle d’Aosta Plan. These ideas crystallized into the doctrine of Comunità or Community set out in his book ‘L’ordine politico delle Comunità published in 1945. He was a great admirer of the US writer and urban theorist Lewis Mumford whose 1938 book ‘The Culture of Cities’ stressed the importance of the region, ‘an area large enough to embrace a sufficient range of interests and small enough to keep these interests in focus and make them a subject of collective concern’.

Olivetti believed that industrialisation and urbanisation were destroying that sense of community and closeness to nature that people felt when they lived in smaller scale surroundings with natural and human boundaries, drawing inspiration from his own experience of living and working in the Canavese region around Ivrea, and the Canton system of government in Switzerland. He proposed that society should be organised in small self-governing communities of between 150,000 and 75,000 inhabitants, centred around industry or technology which would be integrated with housing and agriculture, in effect a form of (liberal) corporatism. He thought that this would be the best way to combine the needs of an industrial society with the values of a traditional one.

These autonomous communities would have their own government, legislature, scientific and academic organisations and, as in Switzerland, they would be organized into a national Federation. They would each represent the ‘spazio naturale dell’uomo’, defined by the natural limits of human social relationships and geography. For a community to function properly, argued Olivetti, its citizens must be in touch with one another and as much as possible with their political leaders. Direct contact with the natural world was also vital. Olivetti was promoting a sustainable society decades before the term was invented.

On his return from Switzerland in 1945 Olivetti founded a journal, a publishing group, and the Movimento di Comunità, keen to disseminate his ideas as Italy was re-building after the war. The Movimento was to be a forum for debate and education, and it established community centres throughout Italy which provided a variety of services as well as spreading the ideas of its founder. It also moved into the political arena by entering the elections in 1953 (not very successfully, although Olivetti became an MP in 1958).

To have some influence on the planning of post-war Italy Olivetti had joined the administration of UNRRA-Casas, the agency tasked with the recovery programme in the country immediately after the war. As part of the decentralisation policy of Comunità he wanted to take some of his production away from the concentrated industrial areas of northern Italy. He decided to build a factory in the impoverished south of the country where he would have the opportunity to put some of his ideas into practice. The site Olivetti chose for the 30,000 sq. metre building was on an elevated position overlooking the Golfo di Napoli, about 15 kilometres west of Naples, in the volcanic area known as the Campi Flegrei.

To design his building Olivetti commissioned Luigi Cosenza (1905-1984), a Neapolitan architect and urban planner, who was a member of the Association of Organic Architecture and a Communist. This was not to be a traditional industrial shed – his brief from Olivetti was to harmonise the requirements of the factory with the landscape, introduce as much natural light and ventilation as possible, and make the most of the views across the bay. Both the plan and clever section achieved this in a spectacular way.

Concept sketch by Luigi Cosenza

Concept sketch by Luigi Cosenza

The cross-shaped plan satisfied the production requirements while integrating the building into the sloping site. The narrow cross-section with fully glazed elevations gave employees direct views to the outside, overlooking landscaped courtyards or the sea. The glazing was shaded from the sun by projecting ledges, and extensive opening vents provided cross-ventilation from the sea breezes. Olivetti’s desire to bring nature into the workplace was masterfully achieved. It must have been wonderful to work there, particularly when you were living in the impoverished south of Italy after the devastation of WW2.

View of main production hall showing the elegant and simple structure designed by the engineers Adriano Galli and Pietro Ciaravolo. Full height windows (shaded where necessary) overlook landscaped gardens. High level vents bring in Mediterranean breezes.

View of main production hall showing the elegant and simple structure designed by the engineers Adriano Galli and Pietro Ciaravolo. Full height windows (shaded where necessary) overlook landscaped gardens. High level vents bring in Mediterranean breezes.

The factory looks more like a modern office park or university campus with its large areas of glazing overlooking gardens or the sea. The integration of the landscape into an industrial environment had never been done before, and has not been attempted again with the same success. The landscaping was designed by Pietro Porcinai to adapt the building to its setting, and a colour scheme was developed by the great Olivetti designer Marcello Nizzoli (creator of the classic Lettera 22 portable typewriter) based on the those found in nearby Pompeii. The site also incorporated a canteen (Mensa on the plan) with views over the sea, a Social Services centre (Assistenza Sociale) with medical and other facilities, a library (Biblioteca), and a training centre for apprentices.

Canteen overlooking the Bay of Naples

Canteen overlooking the Bay of Naples

In line with Olivetti’s social programme a residential neighbourhood for employees was built nearby, also designed by Cosenza. This included primary and secondary schools, a church, shops, cinema and a summer camp, all set in beautiful landscaping.

The factory was hugely successful throughout the 50s and 60s, employing 1,300 workers at its opening and continually expanding to Cosenza’s pre-arranged plan. Following the company’s decline in the 1990s it has now become a technology centre, occupied by Vodafone amongst others. In these times of zero-hours contracts and the minimum wage, criticisms of Amazon, Apple, Samsung, Walmart, and many other firms for their poor working practices, tax avoidance, and vast pay differentials between bosses and workers, it is difficult now to imagine a company that would spare no expense or effort to support the physical and mental welfare of its employees. Pozzuoli was conceived by a visionary industrialist and a left-wing architect who both shared the belief that politics and architecture were inseparable. Sixty years later it still remains the most humane and beautiful factory ever built, a part of the remarkable legacy of Adriano Olivetti.

Adriano Olivetti died on February 27th 1960 from a heart attack on the Milan to Lausanne express at the age of 58. His son, Roberto, took over and the company continued to be at the forefront of design, architecture and employee welfare for another two decades, despite increasing financial problems. It had some notable technological successes such as producing the first personal computer, the Programma 101 in 1965, but following a disastrous hostile takeover of Telecom Italia in 1999 it ended up being swallowed by the much larger company and now produces rather ordinary looking tablets and other electronic devices.

Current Google Earth view of the factory with later extensions to the north

Current Google Earth view of the factory with later extensions to the north

Views of the factory (not luxury offices!), now a technology centre

Views of the factory (not luxury offices!), now a technology centre

“At Pozzuoli, facing one of the most beautiful bays in the world, we built our factory. In its handsome functionalism, its carefully studied organization and its cultural and assistance services which equal those previously established in Ivrea, it bears out our aim of placing technology at the service of man.” AO in ‘Olivetti 1908-1958’

OLIVETTI vs APPLE

Some recent commentators and Italian documentaries have made a rather simplistic connection between Adriano Olivetti and Steve Jobs as entrepreneurs with design-led technology companies who both died at the peak of their careers. This shows a complete misunderstanding and ignorance of Olivetti’s philosophy and approach to business. Not just one of Italy’s leading industrialists or even a philanthropist, he was a socialist intellectual, urban theorist and planner, for whom good design and ‘the product’ were only a part of a much wider picture of how industry could and should contribute to the community and its workers. It is impossible to separate Olivetti the industrialist from (Italian) politics, whereas Jobs never had a serious political thought in his life.

Olivetti’s conviction that a company’s profits should be re-invested for the benefit of the community would be an alien concept to Apple, a firm with a cash pile of $200 billion achieved through rock-bottom labour costs and clever tax arrangements. As is quite evident in Walter Isaacson’s biography (and the recent Danny Boyle biopic), the Product was everything to the obsessive Jobs; his employees were secondary.

You only have to compare Cosenza’s light-filled masterpiece at Pozzuoli to the sunless interior of one of the factories making Apple products (below) to see the gulf between the two companies. The Californian management and designers at Apple will be moving into a spectacular new building by Foster Associates whereas the people who make their iPhones and iPads have had to put up with an appalling working environment which has resulted in protests and suicides.

Unsurprisingly, as businesses are usually short-term profit or dividend driven, Pozzuoli has had no influence at all on the design of industrial buildings. Sixty years later most have become the ‘source of suffering’ that Adriano Olivetti took so much care to avoid with his beautiful building in its gardens overlooking the Bay of Naples, designed to enhance the lives of his workers, rather than ‘diminish their spirit’. Looking at the factory interiors below his words at the opening of Pozzuoli in 1955 seem just as relevant today:

‘…We wanted nature to be part of the life of the factory rather than being excluded by a building which was too large, in which the windowless walls, air conditioning, and artificial light would diminish, day by day, the spirit of those working there…’

Foxconn factory, China

Foxconn factory, China

Clothing factory, Bangladesh

Clothing factory, Bangladesh

Flextronics factory, Texas

Flextronics factory, Texas

Photo and Illustration Credits

Photograph of 1936 Olivetti ICO factory extension – Tommaso Franzolini, founder/director of the Architectural Association Visiting School, Ivrea

Other black and white photographs, plan and section of factory, illustration of original Ivrea factory and early poster – Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti

Coloured sketches by Luigi Cosenza, and colour photographs of factory – Archivio Luigi Cosenza/La Fabricca Olivetti a Pozzuoli book (see below)

Aerial view of factory – Google Earth

Foxconn factory – Shanghai Evening Post undercover reporter Wang Yu

Clothing factory – Fahad Faisal via Wikimedia Commons

Flextronics factory (Google Moto X smartphones) – Google Street View (the factory opened in 2013 after a $25m re-fit and closed at the end of 2014!)

Book

La Fabbrica Olivetti a Pozzuoli (Italian/English text) by Gianni and Anna Cosenza. A really excellent in depth description of the project with superb photographs. Published by Clean Edizioni ISBN 88-8497-020-2 and available from their online shop.

Links

Most of these are in Italian which sadly demonstrates just how quickly Olivetti and Pozzuoli have been forgotten outside Italy.

The story of Pozzuoli from the Olivetti Archive

The Factory with the Most Beautiful View in the World

Bios of Adriano Olivetti:

https://www.storiaolivetti.it/articolo/64-adriano-olivetti/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adriano_Olivetti

Movimento di Comunità (Adriano Olivetti Foundation):

http://www.fondazioneadrianolivetti.it/lafondazione_speciali.php?id_speciali=18

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Community_Movement

Bio of Luigi Cosenza:

http://www.luigicosenza.it/doc/biografia/biografia.htm

Note (1)

Olivetti wrote (unpublished notes for the Olivetti History 1908-58) that ‘Fascism had shattered my aspirations to journalism and my resistance to joining my father’s factory was weakening.’

He had become disillusioned with politics as well:

‘From 1919-1924, during my years at the Polytechnic Institute, I witnessed the failure of the socialist revolution. I can still picture the great parade of two hundred thousand people on May Day 1922 in Turin; but there was no one intellectually capable of channelling this great human impulse towards a better way of life….’ Olivetti History 1908-58