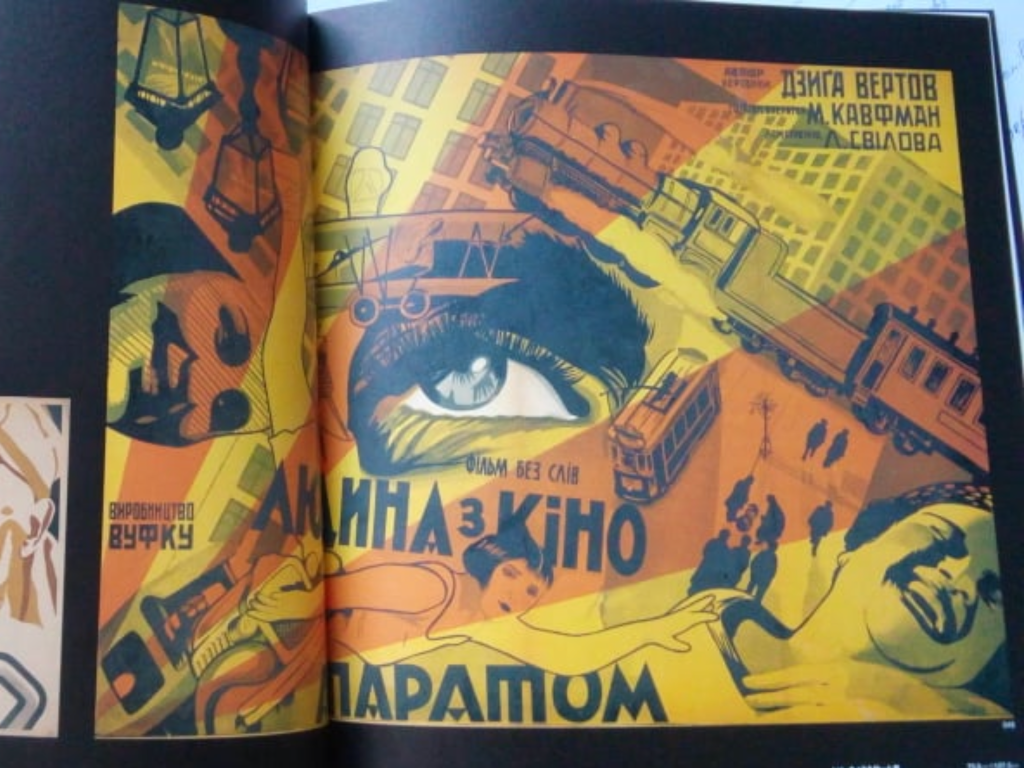

In the spring of 1927 Dziga Vertov* moved to Kyiv to work for VUFKU, the All-Ukrainian Photo Cinema Adminstration (Vse-Ukrains’ke Foto Kino Upravlinnia, ВУФКУ – Всеукраїнське фоtокіноуправління) after being sacked by Sovkino, the Russian equivalent, for being over budget on his film ‘One Sixth of the World’ [1926], and for refusing to present a script for ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ (which he had no intention of writing). Founded in 1922 VUFKU had a reputation for much more adventurous commissioning than Sovkino, and its predecessor Goskino, training, employing, and promoting mostly Ukrainian directors and cinematographers, and their films. VUFKU was effectively closed down in 1930, merged with Soyuzkino (Sovkino’s successor) after accusations of Nationalism, Formalism and other ‘unacceptable behaviour’ by the authorities in Moscow. In less than nine years the studios had produced over 140 full length feature films, and many documentaries, newsreels and animations. Films such as Oleksandr Dovzhenko’s ‘Ukrainian Trilogy’ (‘Zvenigora’ [1928], ‘Arsenal’ [1929], ‘Earth’ (‘Zemlya’) [1930]), and Dziga Vertov’s experimental masterpiece ‘Man with a Movie Camera‘, earned VUFKU an international reputation. It controlled all aspects of the cinematic process including film-making, film processing, screening, publicity, and education. The main studios were originally in Odesa with others in Kharkiv and Yalta. After the earthquake in Yalta in 1927 VUFKU decided to relocate its equipment to large new studios in Kyiv in 1928. These are now the home of the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Film Studio. The studio administration was also based in Kyiv at this time.

*With his wife and brother, Elizaveta Svilova and Mikhail Kaufman. Svilova’s virtuosic editing of ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ is evident, but the latter’s creative contribution to this and earlier films is increasingly recognised (eg the excellent essays about him in the Dovzhenko Centre’s recent book, ‘Ukrainian Dilogy’ 2018).

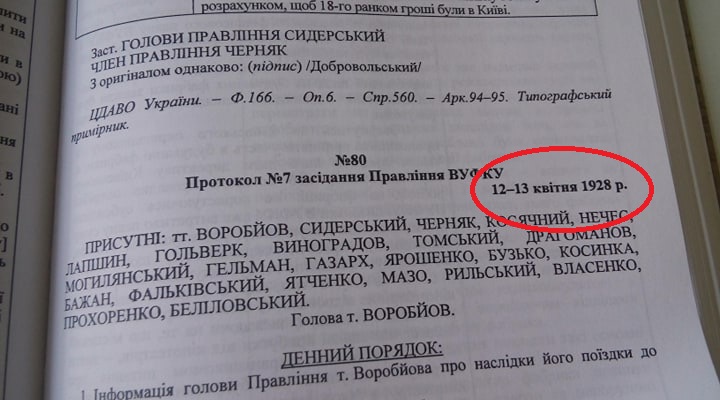

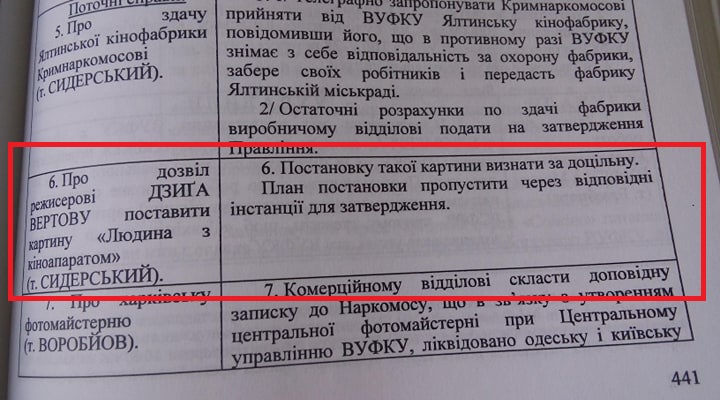

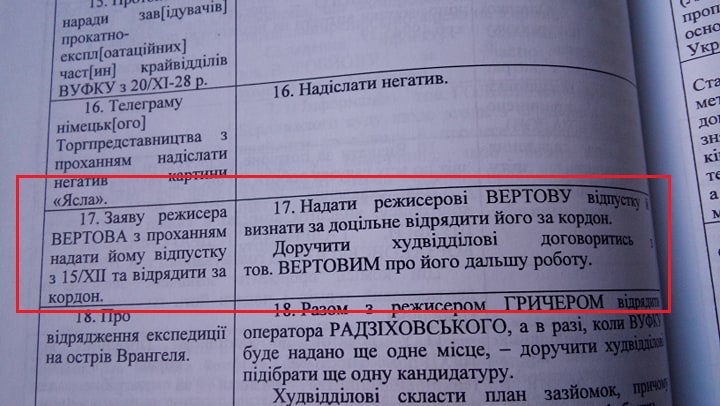

Dziga Vertov’s first commission from the organisation was ‘The Eleventh Year’, a short propaganda film about the development of the electricity industry as part of the Soviet Union’s drive to develop the backward country (ahead of Stalin’s first Five Year Plan that began in 1928). Several sequences for ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ were shot during ‘The Eleventh Year’ filming, and Mikhail Kaufman also used some of the footage for his film ‘Unprecedented Campaign’ [1931]. The VUFKU board were obviously satisfied with this first film as during a meeting held on the 12th and 13th April 1928 permission was granted to proceed with ‘Man with a Movie Camera’.

‘6. About the permission for the director DZIGA VERTOV to shoot a picture ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ (Comrade SIDERSKY).’

‘6. Shooting such a picture is considered appropriate. Pass the production plan through the appropriate authorities for approval.‘

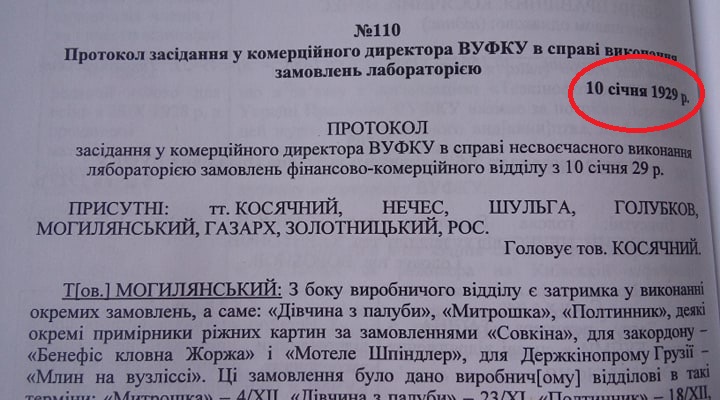

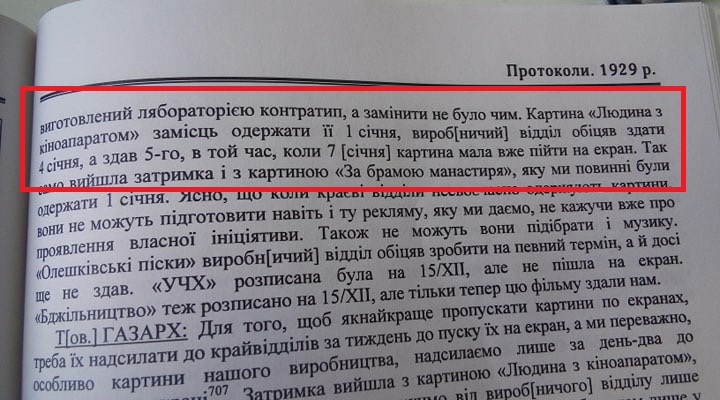

According to the shooting schedule filming began in Moscow in early June and continued to mid-September in Kyiv (see my previous blog post on the locations for details of the schedule). However, a short article in the Kyiv monthly journal Kino No. 11, November 1928, mentions that ‘filming is almost finished’. Editing and production work was presumably going on at the same time, the VUFKU board complaining of slight delays in handing over the film in a minute dated 10th January 1929.

‘The picture “Man with a Movie Camera” instead of receiving it on January 1st* the production department promised to hand it over on January 4th, but submitted it on the 5th, while the picture was supposed to go on the screen on January 7th.’

*A previous minute mentioned January 2nd as the handover date.

VUFKU minutes from ‘Minutes of the VUFKU Board (1922-1930)’, compiled by Roman Roslyak, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, the Rylsky Institute of Art Studies, Folklore & Ethnology, Kyiv. Lyra-K Publishing House, 2017.

THE FIRST SCREENING ON MONDAY 7th JANUARY 1929

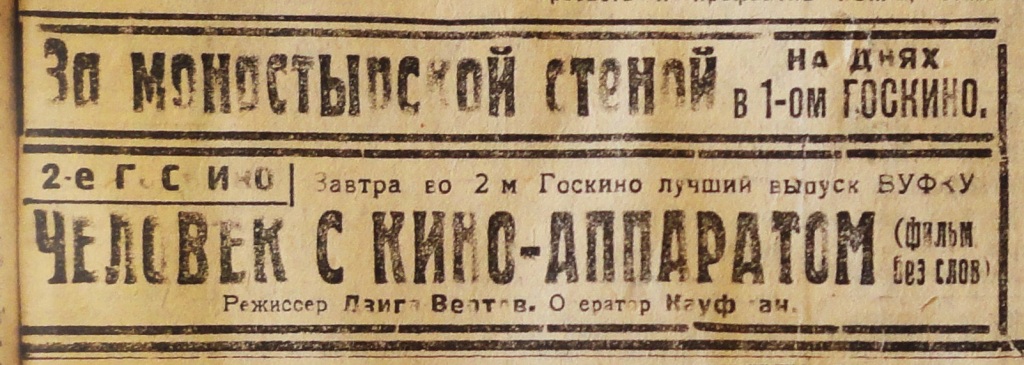

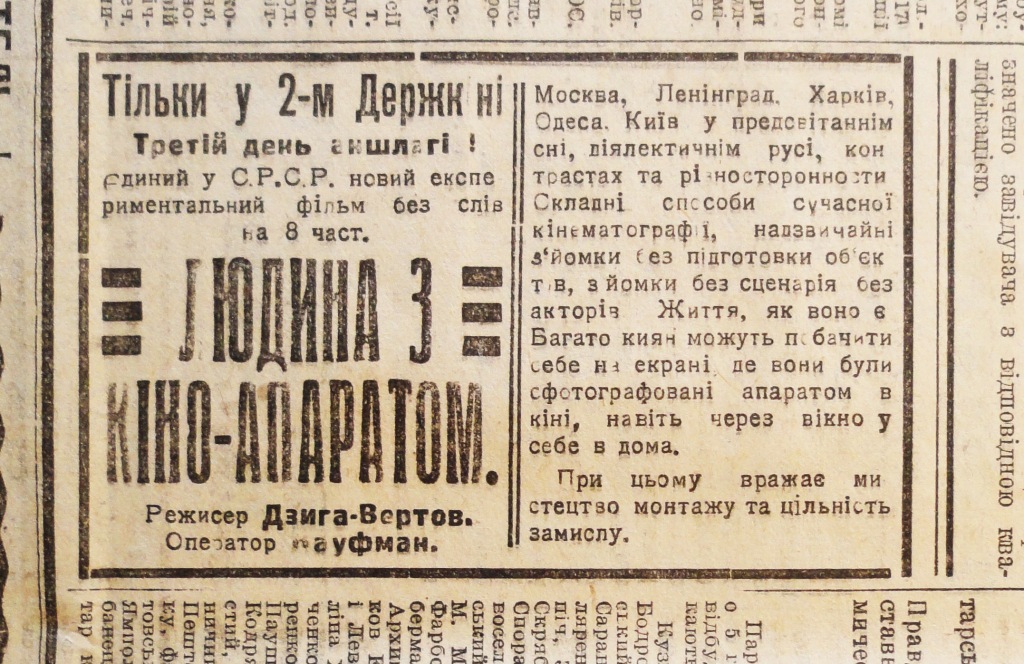

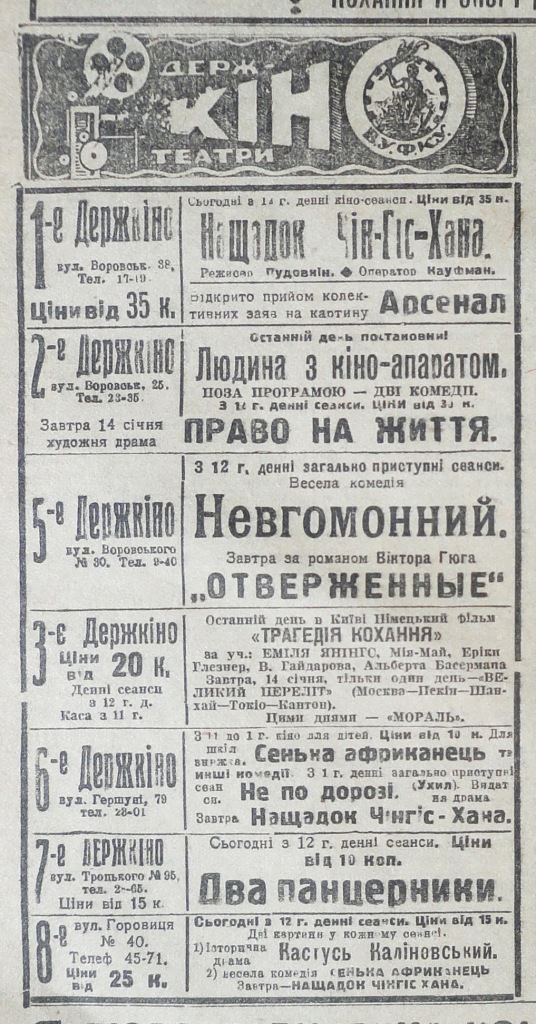

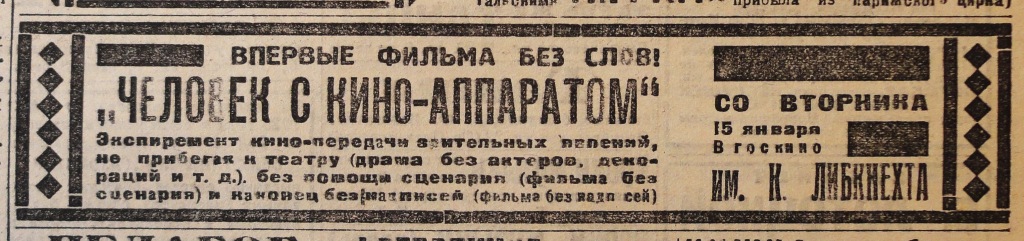

It did make the deadline as the announcement for the first cinema screening of ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ was published on the 6th January 1929 in the Sunday edition of the Russian language newspaper ‘Kievsky Proletary’ (it wasn’t published on a Monday).

A very modest advertisement for the film to be shown ‘tomorrow’ at Goskino No. 2 Cinema with little information except that it was a ‘film without words, Director Dziga Vertov, Cinematographer Kaufman’. The announcement also boasts that the film is the ‘best VUFKU release’, not obvious from the small badly printed advert and screening in the less prestigious Goskino No. 2. Better publicity would follow (see the posters for the Moscow and Berlin screenings).

The Goskino No. 2 Cinema (Держкінo/Derzhkino = State Cinema in Ukrainian) was the re-named Express Cinema on the main boulevard in Kyiv, Khreschatyk (entrance circled above). This was the first cinema in Kyiv, and one of the first in the Russian Empire, opened in 1907 by Anton Shantser. It was a great success and several others followed culminating in his most luxurious cinema, named after himself, which opened on Khreschatyk in 1912. This is the cinema that features in the opening scenes of ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ (see a previous blog post for screenshots and details) so it was a pity that the film could not have been shown there. Both cinemas were confiscated after the revolution and renamed Goskino No. 1 and No. 2. They were destroyed in 1942 when the retreating Red Army blew up the Khreschatyk area of Kyiv.

Although the evidence points to the 7th January being the date of the first screening of the film in a cinema an article [1] on the 12th January 1929 in the ‘Proletars’ka Pravda’ (Ukrainian language) Kyiv newspaper implies an earlier pre-release screening of the film. A remarkably appreciative and insightful review by an anonymous author ‘N.U.’ (likely to be the writer and poet Mykola Ushakov [2]) in the same newspaper on the 21st December is describing the film that must have been seen before it was ready for distribution. Professor John MacKay, Vertov’s biographer, has drawn my attention* to a document in the Vertov archive in Moscow (RGALI f. 2091, op. 1, d. 34) which records the minutes of a ‘discussion of the film “Man with a Movie Camera” by the representatives of the press with the speech by DA Vertov’ dated 7th November 1928. Referring to this in his Academia paper ‘Man with a Movie Camera: an Introduction’, 2013 (p. 5, fn. 8), Professor MacKay notes that ‘the speakers at this session were largely enthusiastic about the film, in contrast to an earlier debate in Khar’kov, where (according to Vertov) speakers declared that he should be prevented from working further, and that the film was a “criminal” waste of government funds’.

This seems to be the only record of pre-release screenings of the film but as filming appears to have still been going on in October (Kino article above), and the VUFKU production department only handed the release print over for public screening on the 5th January 1929, the film must have been incomplete at this stage. It also seems odd that Mykola Ushakov’s enthusiastic review was not published until six weeks after the November screening. It therefore seems likely that there was another screening in late December to approve the film for release. Unfortunately, there are no details of any pre-release screening in the VUFKU protocols.

*email to author

[1] [2] See Notes at end

Anna Onufriienko, Research Scholar and co-curator of the exhibition ‘VUFKU: Lost & Found’, at the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre in Kyiv comments:

‘Щодо показу в грудні, думаю, це ймовірно, можливо, показ був внутрішній на засіданні приймальної комісії ВУФКУ, які обговорювали і дозволяли випуск фільму в прокат. Подібні засідання були звичною практикою. Наприклад, у книзі Українська дилогія, яка сподіваюсь, до вас невдовзі потрапить, є стенограма такого засідання щодо фільму “Навесні”. Там були присутні різні представники ВУФКУ, а також журналісти, письменники. Щодо такого показу в протоколах ВУФКУ нічого немає.’

‘As for the screening in December, I think it is probably possible that the screening was internal at a meeting of the admissions committee of VUFKU, which discussed and allowed the release of the film for rent. Such meetings were common practice. For example, in the book ‘Ukrainian Dilogy’….there is a transcript of such a meeting on the film “In Spring”. There were various representatives of VUFKU, as well as journalists and writers. There is nothing about such a show in the protocols of VUFKU.’

THE FIRST REVIEW OF ‘MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA’

‘Proletars’ka Pravda’ 21st December 1928

The Ukrainian transcription from the review by Mykola Ushakov and a full translation are at the end of the post. Ushakov is full of praise for the film, describing it as a masterpiece.

“…Dziga Vertov himself calls his film only an experiment. Perhaps this is excessive modesty. Man with a Movie Camera almost goes beyond the scope of laboratory research. This is a truthful picture, which excites not only by the freshness of its view of the material, not only by its formal achievements but also by its thematic depth. Many directors in the USSR and abroad will extract material from it in parts, and dozens and hundreds of young filmmakers will learn from it photogeny, interpretation of nature, editing and cinematographic art.

VUFKU is destined to give world cinema a new masterpiece. Let VUFKU use it to provide Vertov with a further opportunity to experiment in this way. These experiments will become the pride of Ukrainian cinema.”

ANNOUNCEMENTS FOR THE REST OF THE WEEK IN KYIV

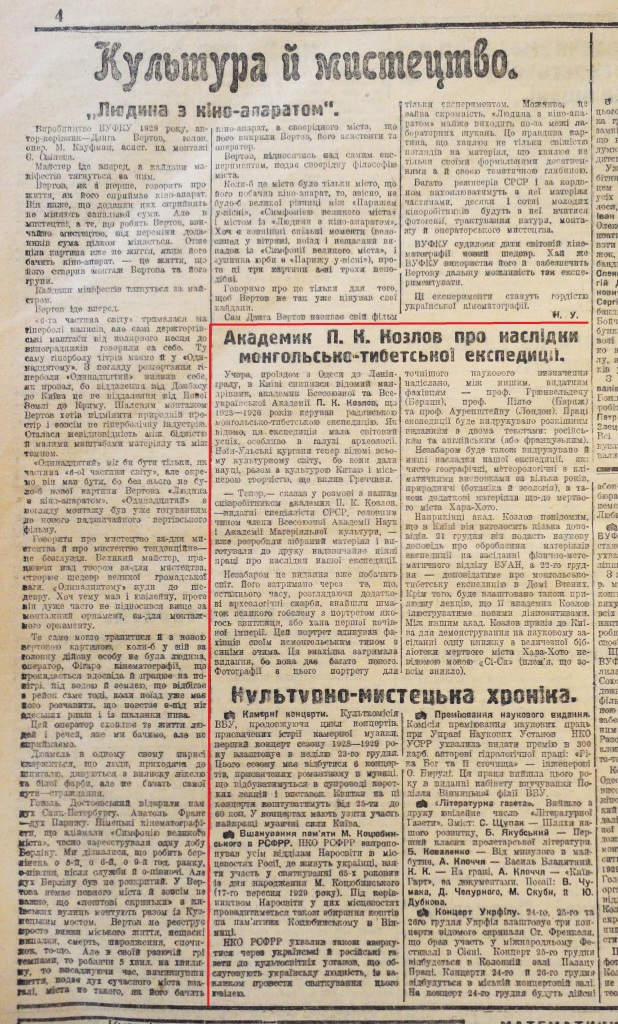

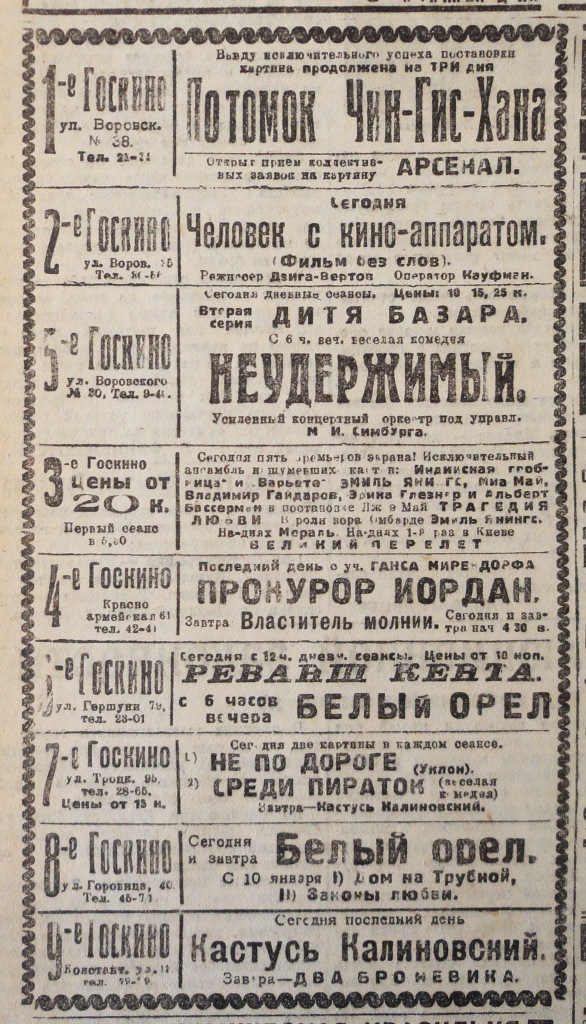

Advertisements in Russian from the ‘Kievsky Proletary’ newspaper and in Ukrainian from the ‘Proletars’ka Pravda’ newspaper.

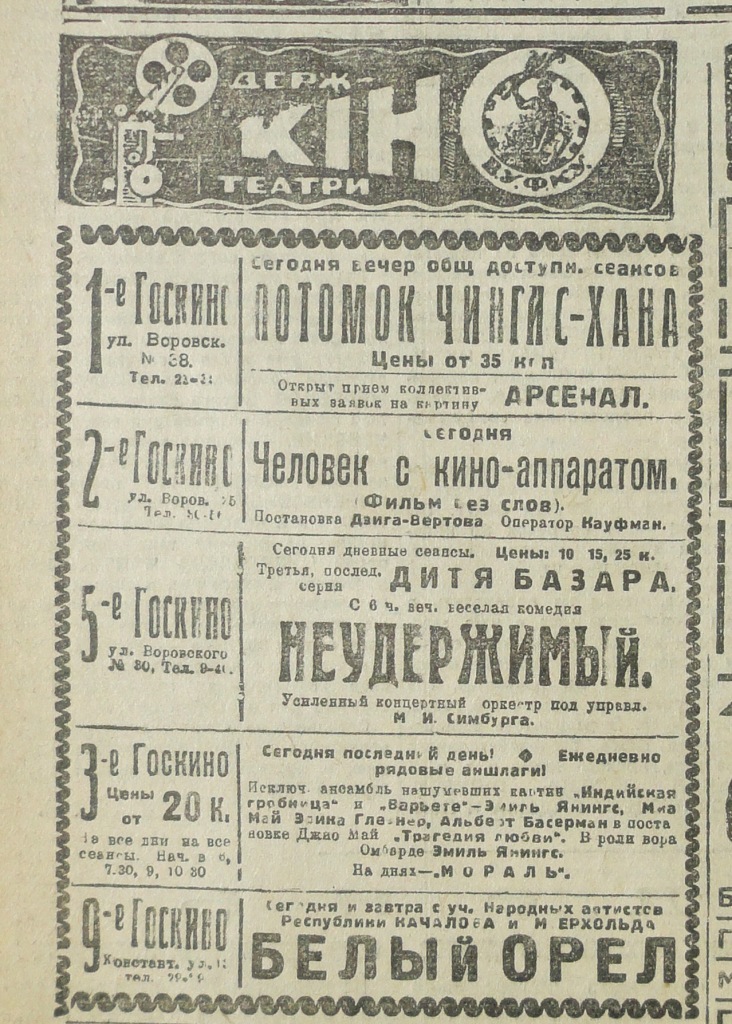

TUESDAY 8th JANUARY 1929

The second announcement for the film has even less information than the first, omitting ‘best release from VUFKU’. Goskino No. 1 Cinema is screening Vsevolod Pudovkin’s ‘Storm over Asia’ (aka ‘The Heir to Genghis Khan’) [1928] (with a mention of Dovzhenko’s ‘Arsenal’ below), stiff competition for ‘Man with a Movie Camera’!

WEDNESDAY 9th JANUARY 1929

Announcements in both papers, proclaiming that the third day is sold out! ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ is described as ‘the only new experimental film in the USSR without words in 8 parts’ (sic). There is much more information about the film this time in rather florid language: ‘Moscow, Leningrad, Kharkov*, Odessa, Kiev are in anticipation of a dream (of) dialectical movement, contrasts and versatility. The most sophisticated techniques of modern cinema, extraordinary filming without any preparation of props, without a script, and without actors. Life as it is. Many Kievans can see themselves on the screen, where they were photographed by the camera in the cinema, even through a window at home. At the same time the art of film editing and the integrity of the design are impressive.‘

These adverts are perversely printed at right angles to the page for some reason, perhaps to make them stand out.

*I have only found evidence of one Kharkiv location in the film. See my blog post on the locations.

THURSDAY 10th JANUARY 1929

Announcements for the film in the newspapers on this day have not been found. Perhaps it was sold out again and there was no need to advertise.

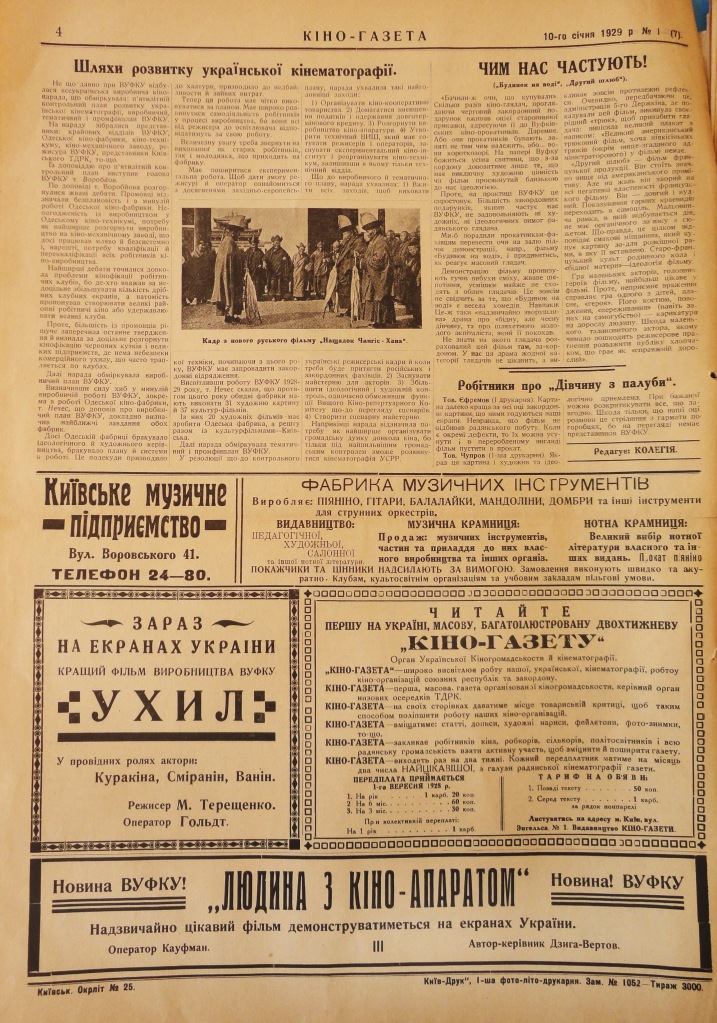

There is an advertisement for the film in the 10th January edition of the monthly Kiev journal ‘Kino-Gazeta’ at the bottom of page 4. This proclaims: ‘VUFKU News! An extremely interesting film will be shown in Ukraine. Cinematographer Kaufman, Author-Director Dziga Vertov’.

FRIDAY 11th JANUARY 1929

Back to the same basic announcement of the 8th January.

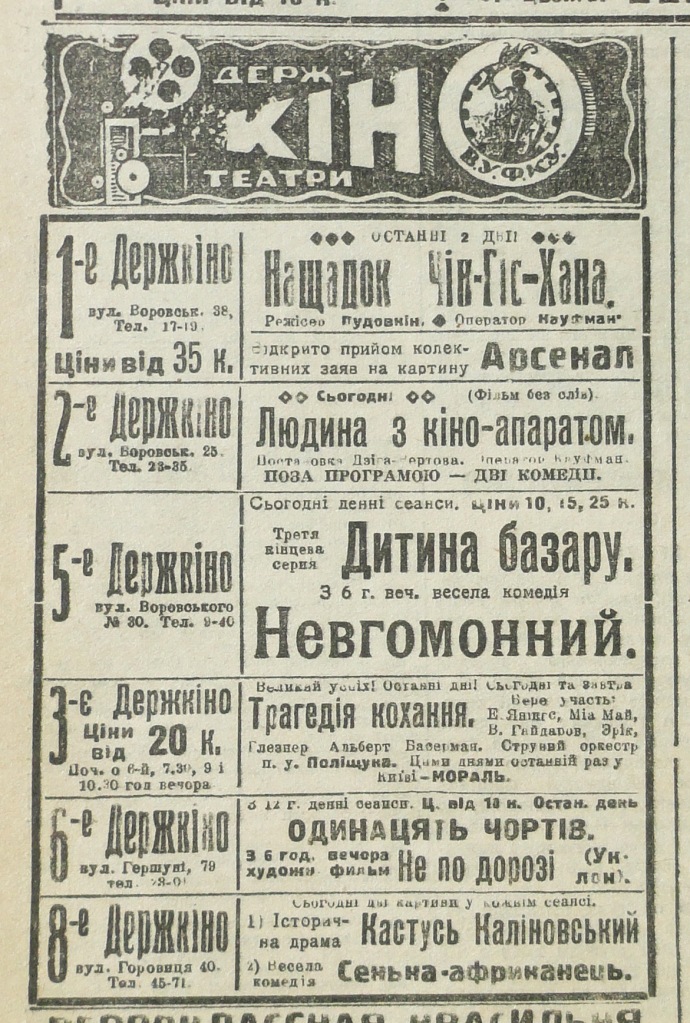

SATURDAY 12th JANUARY 1929

Interest in the film was waning perhaps as two comedies have been added to the programme to encourage Saturday cinema goers!

SUNDAY 13th JANUARY 1929

This was the last day of the film in Kyiv and the following Monday’s screening was being promoted in larger type. This was an ‘artistic drama’ entitled ‘The Right to Life’, a 1928 Sovkino film directed by Pavel Petrov-Bytov. It was about ‘the battle against protectionism in the production process during the NEP years’ which does not sound much like an ‘artistic drama’ but the story-line of a village girl being exploited when she comes to the city is similar to Boris Barnet’s more famous 1928 film ‘The House on Trubnaia’. [source: Julian Graffy]

KHARKIV PREMIERE – TUESDAY 15th JANUARY 1929

The print of the film must have then gone straight to Kharkiv as the first screening in the Ukrainian capital at the time was announced in the Sunday 13th January edition of the Khar’kovsky Proletary newspaper for the following Tuesday at the Goskino ‘K. Liebknecht’ cinema. The digital press archives for Kharkiv are incomplete so I am unable to discover how long the film was shown, and find reviews.

The announcement proclaims (in Russian) that this is the ‘first film without words’, and goes on to copy the titles at the beginning of the film – ‘An experiment in the cinematic transmission of visual phenomena, without resorting to theatre (a drama without actors, sets etc), without the help of a script (a film without a script), and finally without intertitles (a film without intertitles).’

Early 1900s view of Sumska Street, the main street in the city, showing the location of the cinema.

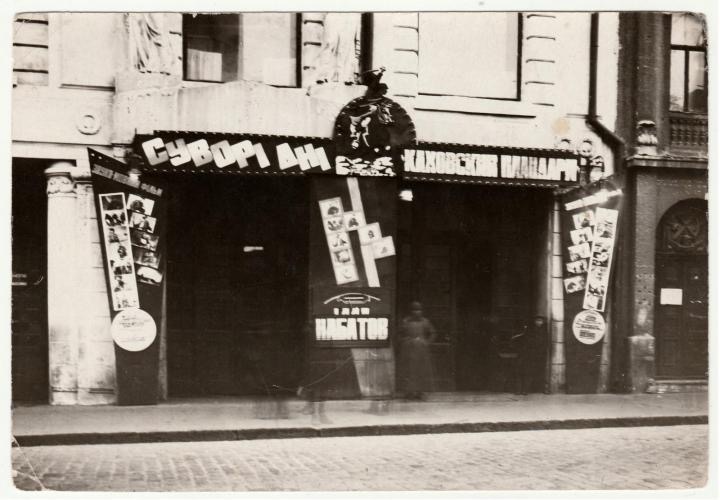

The cinema was opened in 1913 as the ‘Empire’, confiscated after the Revolution and re-named after the 19thC Prussian socialist politician and theorist Karl Liebknecht. [1930s photograph of the entrance].

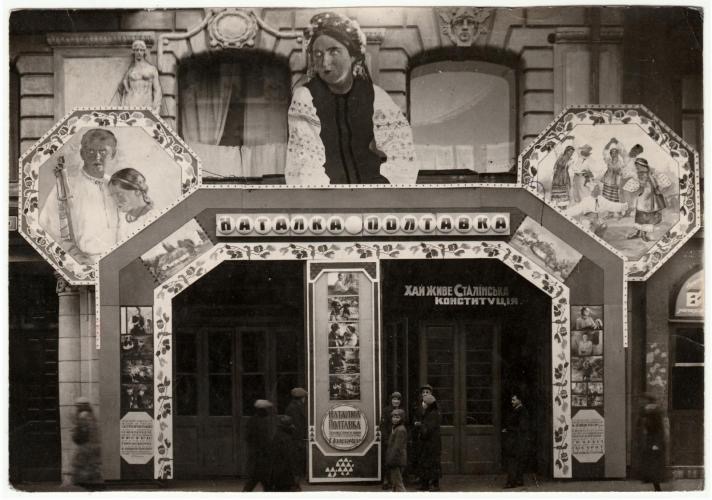

An extravagant display of folk paintings and costumes to advertise the 1936 film of ‘Natalka Poltavka’, the 1819 nationalist play by Ivan Kotlyarevsky turned into a popular operetta by Mykola Lysenko in 1889. This first adaptation of an operetta in the Soviet Union was directed by Ivan Kavaleridze. A surprising production given the political situation of Ukraine at the time as the anti-nationalistic ‘Great Terror’ had commenced but apparently Stalin liked the operetta.

MOSCOW PREMIERE – TUESDAY 9th APRIL 1929

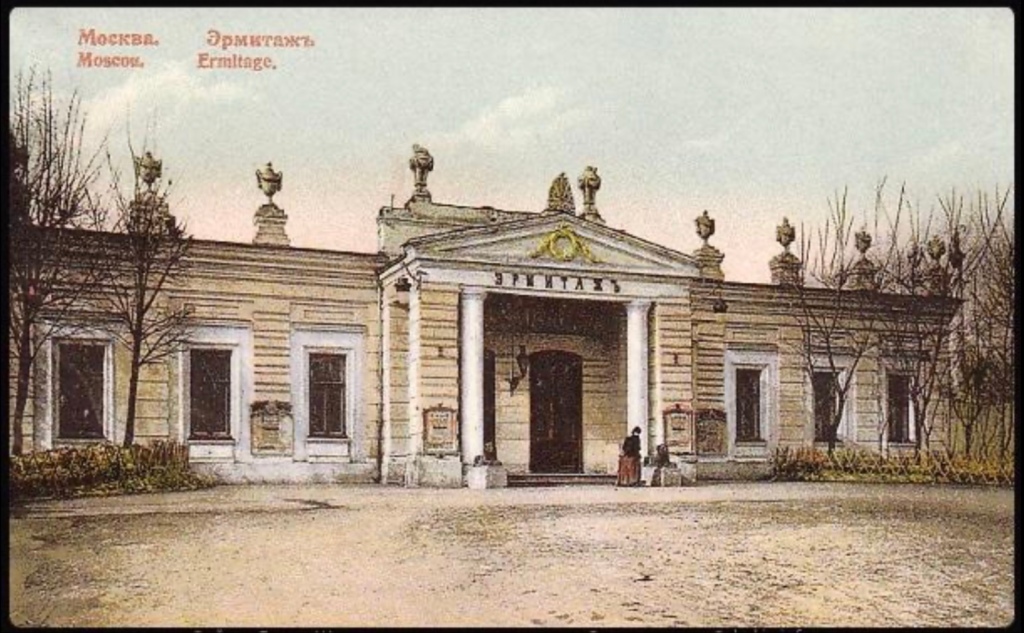

The Moscow premiere of the film was at the Hermitage Theatre in the Hermitage Garden and Tverskaya 46 Cinema on the corner of Tverskaya and Strastnaya Square. There was a preview of the film in the previous month attended by ‘experts in the art of film and from literature, theatre, and art circles’ as reported by the German Die Form magazine (see German screening).

A 19thC postcard of the Hermitage Theatre, one of the pavilions in the Hermitage Garden, located in the north of the city near the Garden Ring. Established in 1894 the garden became an important cultural centre with several theatres located in buildings in the garden or nearby. The Hermitage Theatre (not to be confused with its more famous St Petersburg namesake) was the venue for the first showing of a film in the city (‘The Arrival of a Train’) by a travelling Lumière operator in 1896. Nationalised in 1918 it was rented by a group of entrepreneurs in the NEP period for a variety of entertainment events, including film shows.

Screenshot [00:16:13] from the film showing the corner of the Tverskaya 46 Cinema at the junction of Strastnaya Square and Tverskaya street. The poster of a man in spats and large ‘disc’ with the cinema name can be seen on the building behind the motorcycle and sidecar in another screenshot below. The full poster as seen below is on the wall to the right of the kiosk.

Screenshot [01:04:31] showing the cinema on Strastnaya Square.

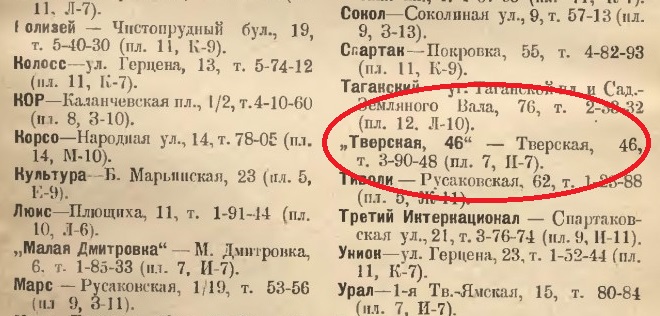

The cinema’s entry in a 1929 Moscow directory.

The posters are advertising the 1928 film ‘Engineer Elagin’, directed by Vladimir Feinberg. The man in spats probably depicts the engineer’s traitorous son in the pay of foreign intelligence, who sabotages his father’s factory and kills a worker. Engineer Elagin forces his son at gunpoint to give himself up! [Many thanks to James Mann for tracking down the poster and to Julian Graffy for information on the film]

The first* announcement for the film in ‘Pravda’ on Sunday 7th April 1929 advertising the premiere on the 9th.

The advertisement for the film on the day of the premiere. Unclear in parts but much of the rather sensational text is decipherable: ‘Today, the premiere of the first film in the SSSR without words. Man with a Movie Camera, Author supervisor Dziga Vertov, Chief cameraman M. Kaufman, Assistant editor E. Svilova. A VUFKU Production. Hermitage VUFKU, Tverskaya 46. Amazing adventures of a film cameraman. On land, on water, underground and in the air, for the first time – the TRANSFORMATION of a cameraman from a GIANT into a midget and vice versa. A Cinema GULLIVER…People in the air, a FROZEN horse, FILM-RESURRECTION of people and animals…The man is in danger…a tram over the auditorium…HELP…EXPLOSION of time. What happened to Theatre Square? The rebellious pendulum. Chasing time. Up to 1000 kilometres an hour…Up to 15 minutes per minute.’

*Preliminary ‘teaser’ advertisements were placed in Pravda from the end of March.

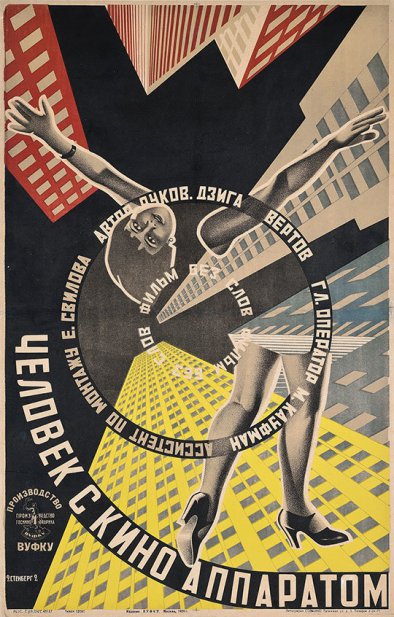

In contrast to the paltry announcements in the Kyiv and Kharkiv press VUFKU obviously thought it worthwhile to commission the renowned graphic artists Georgii and Vladimir Stenberg to design a poster for the Russian screening of the film. The result is a masterpiece, surely one of the greatest film posters of all time. It perfectly captures the spirit of the film’s breakneck journey through the city, using a spiralling motif with the letters suggesting the frames of a film. Clearly produced to promote the film for the Moscow premiere the description of Vertov et al matches that in the Pravda advertisement. Printed (by Sovkino) in an astonishingly large edition of 12,000.

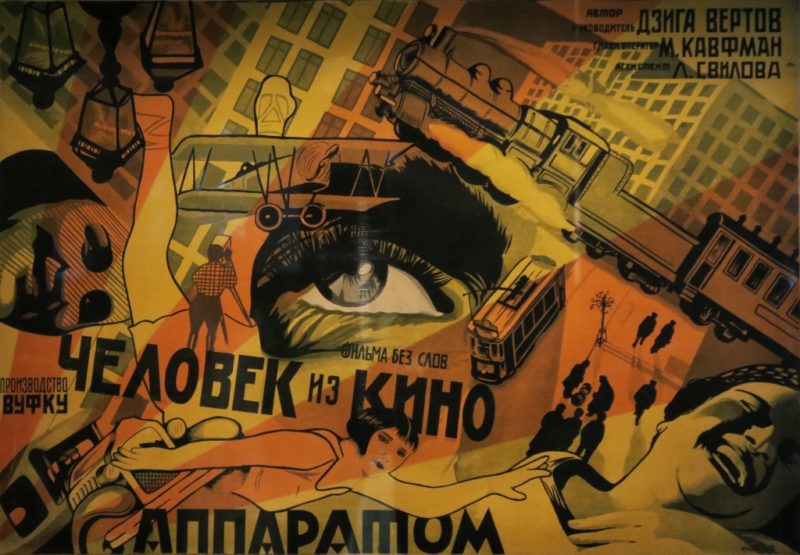

The second Stenberg brothers poster for the film doesn’t quite match the virtuosity of their first but is still a wonderful graphic representation of images from the film (though the ‘gun’ silhouette is clearly designed to attract an audience as it is only a fleeting image in the film). The ‘camera eye’ is a brilliant device, and the Debrie camera and tripod are very accurately depicted.

This poster for the film by M. Chelovski is exhibited in the Cinémathèque française in Paris, but I have no information about it or the designer. In the Russian language but an odd rendering of the film title using ‘из’ (of) and ‘Kaufman’ is also spelled incorrectly. The alternative spelling of аппаратом is odd as the ‘m’ replacing ‘t’ in Cyrillic is normally only used in handwriting or an italic font. [photograph courtesy of the Cinémathèque française]

Anna Onufriienko has found a Ukrainian version of the poster seen in a catalogue of the ‘Ippei Fukura Collection’ of Soviet posters at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. The ‘with’ in the film title is now correct but the misspelled ‘Kaufman’ remains. The Dovzhenko Centre does not know of any other Ukrainian posters for the film. The only other publicity I have come across is a newspaper or magazine advertisement in the Vertov Archive at the Austrian Film Museum.

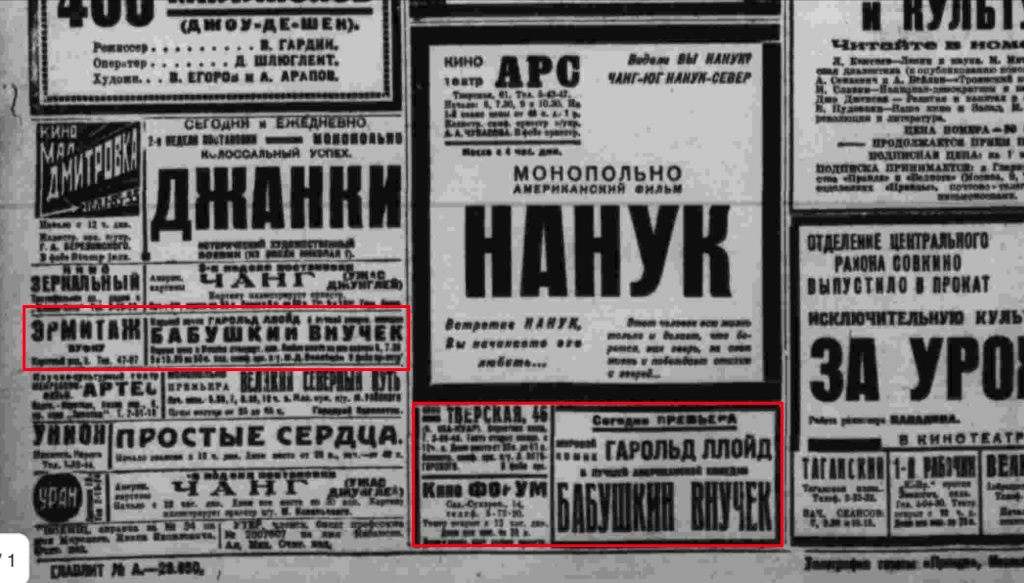

‘Man with a Movie Camera’ was on for a week, replaced on the 16th April in both cinemas by an old Harold Lloyd film ‘Grandma’s Boy’ (1922). Also on show (‘exclusively’) at the famous ARS Cinema on Arbat was another 1922 film ‘Nanook of the North’.

This is the actual poster advertising ‘Grandma’s Boy’ at Tverskaya 46 on the 16th April 1929.

Chapters 24 & 25 in ‘Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties’ (edited by Yuri Tsivian) has several articles on the film, some with complaints about the short run at both cinemas. Konstantin Feldman in Vecherniaia Moskva, 18th April 1929, (chap. 25, p. 349) writes that ‘Our readers remember the campaign which Vecherniaia Moskva had to wage so as to achieve the cinematic release of Dziga Vertov’s film “Man with a Movie Camera”. Our exhibitors and cinema administrators – experienced specialists and connoisseurs of public taste – peremptorily decided that this film would not “get through” to the mass viewer. When it was finally put on in two large Moscow cinemas, Dziga Vertov’s film brilliantly refuted these gloomy prophecies. For a whole week the film did good box office at both theatres, competing successfully against foreign “hits”‘.

However, Feldman complains, despite this great success the film was immediately withdrawn from the screens of the two cinemas. He sarcastically says that if they were showing ‘popular’ films everything would have been ‘arranged for the better’ and they would have been kept on for a second and third week. ‘The film is being taken off the screen by force. We must hurry and expedite the release of such a significant film as “Grandma’s Boy” with Harold Lloyd himself. The mistake goes beyond the bounds of the permissible. We have before us the fact of stubborn opposition to bringing a work by a Soviet master to the mass viewer. It is time to draw conclusions from this whole long drawn-out story.’

See below for further reviews from the book, and publication details.

THE FIRST SCREENING OF THE FILM OUTSIDE THE SOVIET UNION

VUFKU Board Meeting Minute 17, Protocol 53, December 11th 1928.

’17. Statement of the director VERTOV with a request to give him leave to go abroad from the 15th December.’

’17. [resolved] to give the director VERTOV a vacation and it is expedient to send him abroad. Instruct the Art Department to agree with VERTOV on his further work.’

VUFKU minute from ‘Minutes of the VUFKU Board (1922-1930)’, compiled by Roman Roslyak (see end notes for details).

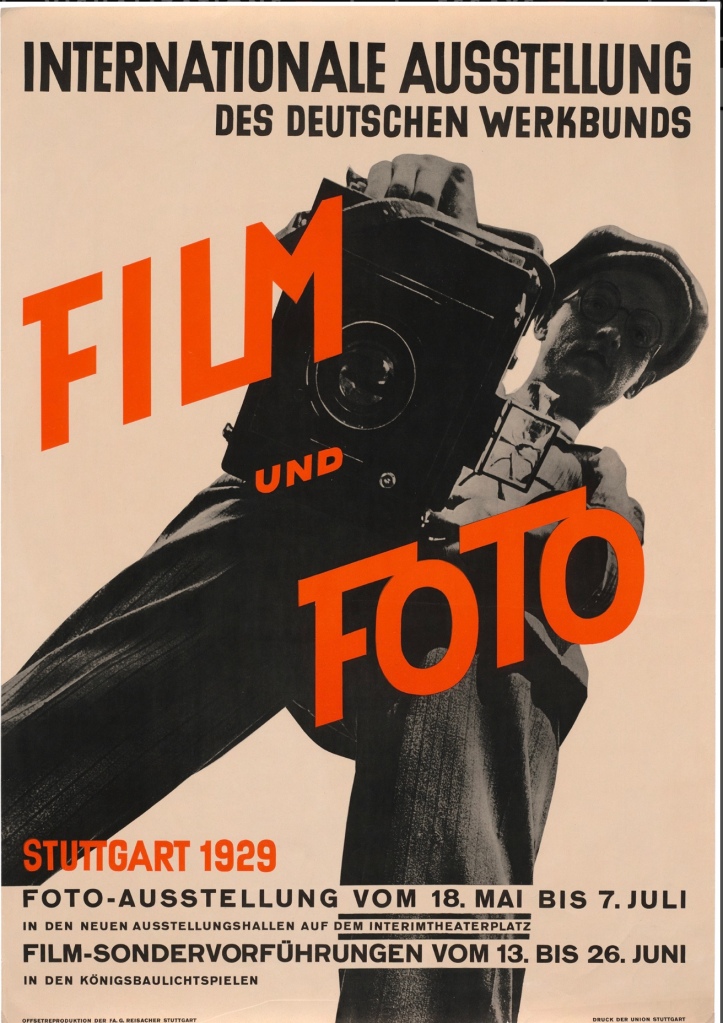

FILM UND FOTO EXHIBITION, STUTTGART, MAY – JULY 1929

In May 1929 Dziga Vertov took a print of ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ with him on a tour of Europe to promote the film. It isn’t clear if this trip was a delayed result of the minute above or further permission had been granted. The tour was largely organised by the contacts of Vertov’s friends El Lissitzky and his German wife Sophie Küppers. The Lissitzkys had been commissioned to design the Russian Room at the seminal 1929 Stuttgart exhibition ‘Film und Foto’. An unprecedented event that showcased contemporary photography and cinema from Europe, the Soviet Union and the USA, by all the leading practitioners of the day. The curator of the film section of FiFo, Hans Richter, wanted to promote film as a serious art form and many prominent film-makers took part in the exhibition, including Charlie Chaplin, Marcel Duchamp, Viking Eggeling, and Walter Ruttmann. Films by Sergei Eisenstein, Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Vsevolod Pudovkin, Esfir Shub, and Dziga Vertov were screened in the Russian Room.

Unlike the rest of the exhibition The Russian Room (above) combined both film and photography showing work by contemporary Soviet directors alongside photographs by Aleksandr Rodchenko and others.

HANOVER, 3rd and 4th JUNE 1929

The first screening of the film outside the Soviet Union in a cinema was in Hanover according to an announcement in the Hannoverscher Anzeiger newspaper of the 1st June 1929. It was only on for two days, with talks by Vertov and ‘other work’ being shown, as the print was presumably needed for ‘Film und Foto’. It was not screened in a conventional street level cinema but in the huge dome of the planetarium at the top of the newspaper’s offices, the Brick Expressionist Anzeiger-Hochhaus building (below). Designed by Fritz Höger, and completed in 1928, the building was one of the first high rises in Germany, hence its name. In December 1928 a temporary cinema in the planetarium was opened under the name ‘Planetarium-Lichtspiele Kulturfilmbühne‘ (stage for cultural films), with 210 seats1. The reason for this first screening in Hanover seems to have been the Lissitzky’s contacts at the Kestner Gesellschaft, the city art gallery founded in 1916 to promote modern art2. Sophie Küppers-Lissitzky came from Hanover and her first husband had been the director of the gallery for many years3.

1Hanover City portal and Hochhaus-Lichtspiele website. ‘The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum’, p. 262, describes the film ‘being projected into the dome of the planetarium’ but this seems unlikely and a misinterpretation of the location.

2‘Hannover in 3 Tagen: ein kurzweiliger Kulturführer’, Peter Struck, Schlütersche, 2008.

3‘The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum’, p. 262.

Announcement in the Hannoverscher Anzeiger on 1st June 1929 advertising the screening of ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ in the Planetarium on Monday 3rd and Tuesday 4th June, at 8:20pm. ‘As well as this film Vertov will show other work. Vertov will also personally speak about his creative endeavours’. [courtesy of ‘The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum’, ref: Pr De 005].

During his second European trip Dziga Vertov had also been invited to give a talk at the Kulturfilmbühne on the 7th and 8th October 1931 about his first sound film ‘Enthusiasm: the Donbas Symphony’ but this had to be cancelled after the film was banned in Germany on October 5th [‘The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum’, letter ref: B013].

Vertov also gave talks about the film and Kino Eye to audiences in Berlin, Munich1, and Frankfurt2. Germany was the centre for film production and photographic manufacturing in Europe at that time, and the giant UFA Studios in Berlin were the most advanced in the world. This made the city the most important venue for a screening of ‘Man with a Movie Camera‘ during the tour.

1 ‘The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum’, p. 35 & pl. 19.

2‘Lines of Resistance’ chap. 28, p. 378.

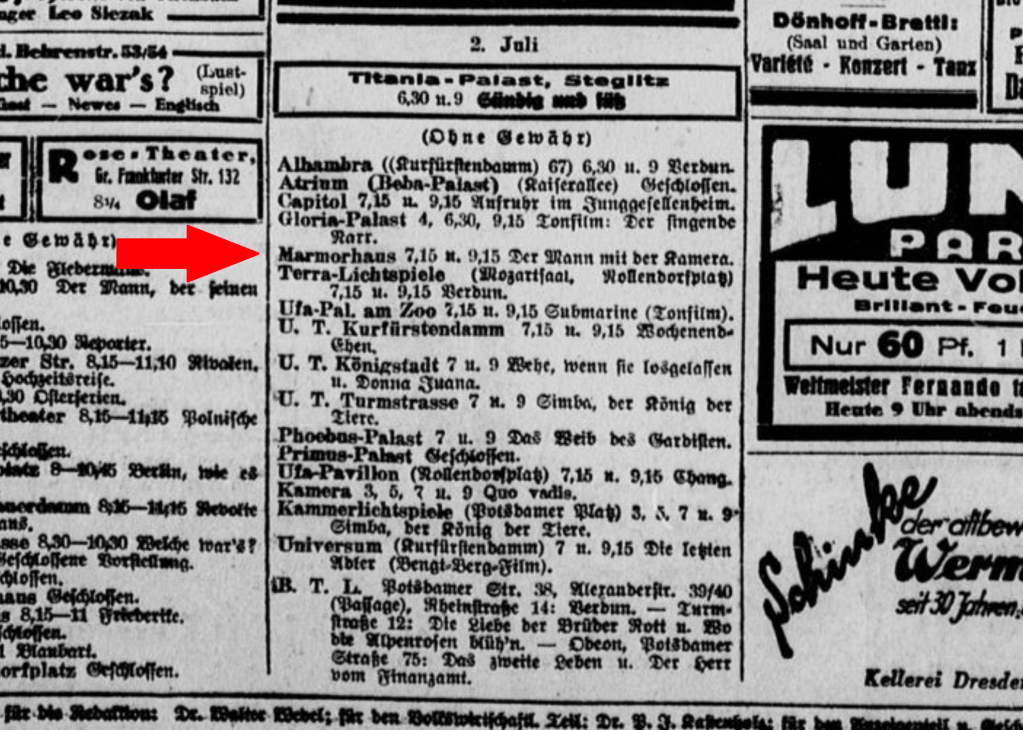

BERLIN PREMIERE, TUESDAY 2nd JULY 1929

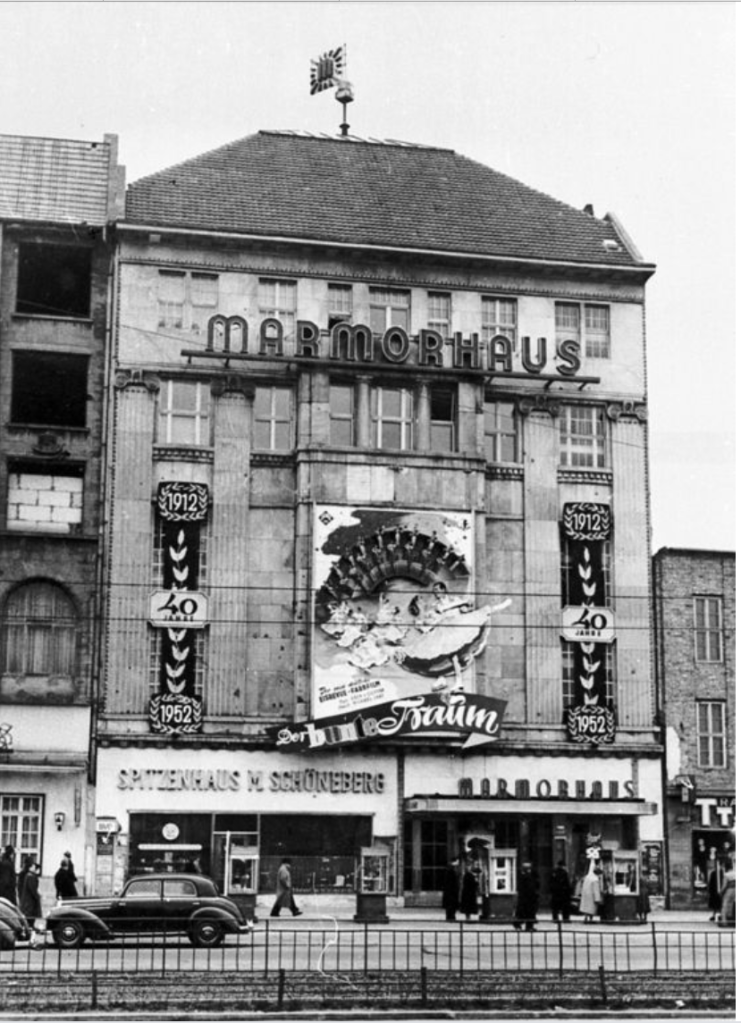

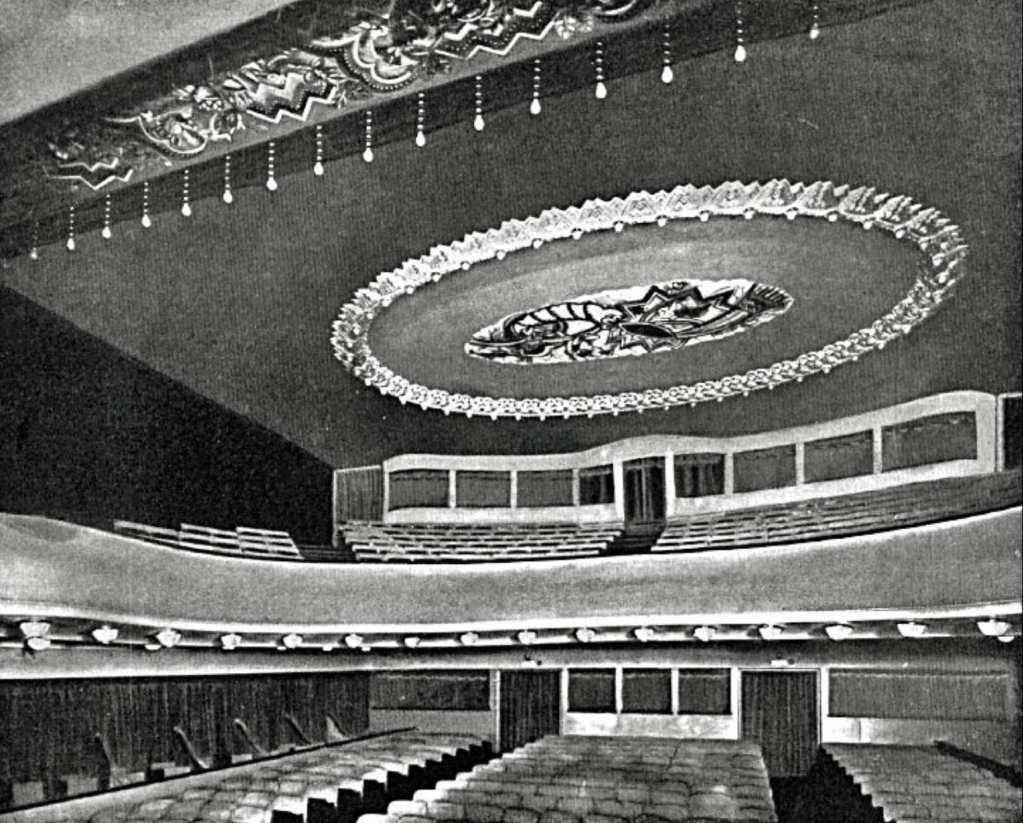

Following the film’s showing at ‘Film und Foto’ and Hanover the Berlin premiere of ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ was on the 2nd July at the Marmorhaus cinema (named because of the marble facade) on Kurfürstendamm. Built in 1912 on the most prestigious avenue in the city it was often the venue for the first screening of new films, including ‘The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari’ [1920] and ‘The Head of Janus’ [1920], the interior designed by the Expressionist painter and set designer César Klein making it a suitable location for both. Dziga Vertov also gave a talk at the venue on the day of the premiere1.

1‘Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum’, ref: Pr De 053.1.

A much better advertisement for the film than the Soviet papers could manage in the 29th June edition of Film Kurier [courtesy of ‘The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum’, ref. Pr De 049.IV].

The advertisement of the premiere of ‘Der Mann mit der Kamera’ at the Marmorhaus Cinema in the 2nd July 1929 edition of the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung newspaper. Performances at 7:15 and 9:15.

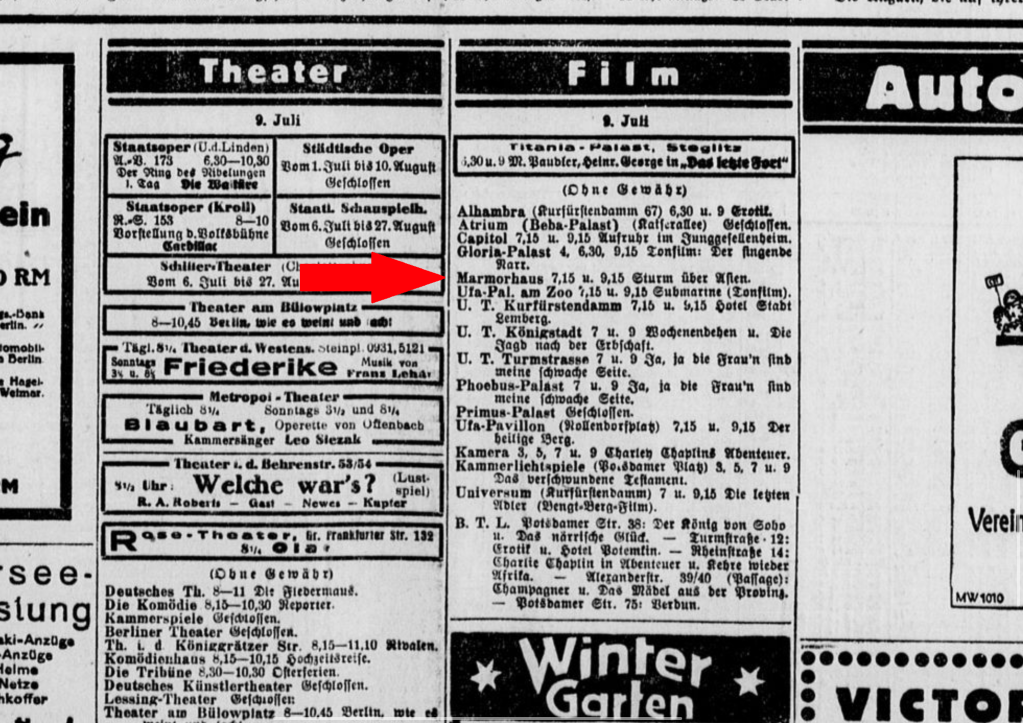

The film was at the Marmorhaus for a week, replaced on the 9th July by another Soviet film premiere, Vsevolod Pudovkin’s ‘Storm over Asia’ (the film that occupied Goskino No.1 Cinema in Kyiv during the screening of ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ back in January!).

The Marmorhaus Cinema in 1952 (I cannot find any suitable contemporary views of the building).

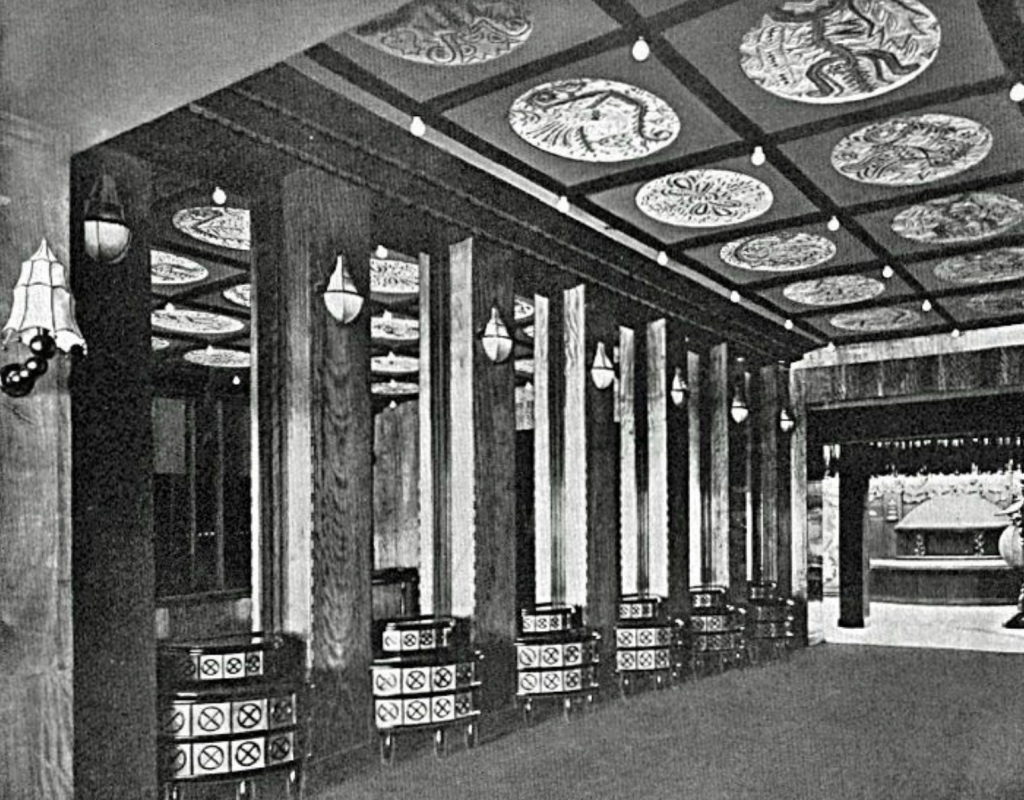

Interiors of the cinema (unknown date). [photographs: Oleg Andreev]

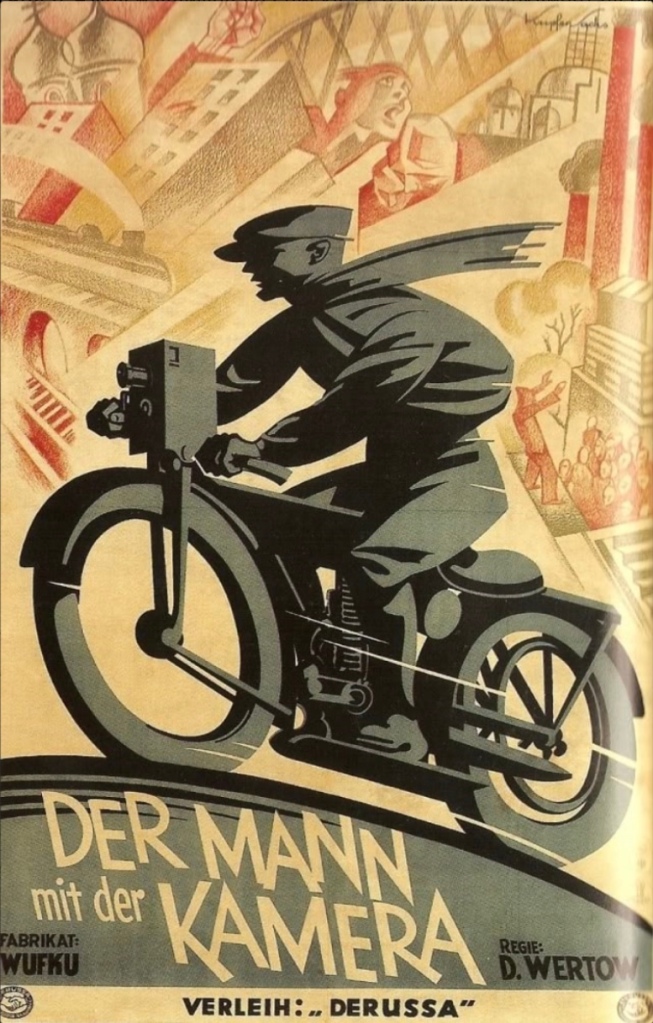

Another superb poster for the film, designed by Julius Kupfer-Sachs, showing the cameraman on a motorcycle speeding through an Expressionist city. According to a stamp on the poster it was approved by the Berlin film censors on the 24th June 1929, a week before the premiere [source: Austrian Film Museum Collection].

It seems Dziga Vertov may have designed a very good photo montage, featuring stills from the film, for promoting it in Germany.

EARLY REVIEWS OF ‘MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA‘

The popular narrative (eg Wikipedia, Senses of Cinema etc) is that ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ was poorly received by both critics and the public on its release in the Soviet Union. Sergei Eisenstein’s comment that the film was ‘pointless camera hooliganism’ is well known. The reality was largely the opposite, typified by the first, very enthusiastic, review of the film by Mykola Ushakov written after a pre-release screening in Kyiv. After the first rather modest announcements in the local papers VUFKU obviously thought the public reaction to the film made it worthwhile to commission a poster (and a second) from the leading designers of the era, the Stenberg brothers, and have 12,000 of it printed. As noted above the Moscow screening was counted a success by critics, who complained the film was taken off too soon.

The principal reference to writings by and about Dziga Vertov is ‘Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties’ (edited by Yuri Tsivian with translations by Julian Graffy and research by Aleksandr Deriabin, published by Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2004) which includes contemporary articles and reviews of the film in the Soviet Union and the West. The majority of these are very positive about the film and its director.

THE FIRST (PRE-RELEASE) REVIEW OF THE FILM

21st DECEMBER 1928 by MYKOLA USHAKOV

Transcribed from:

Пролетарська правда. – 1928. – 21 грудня.

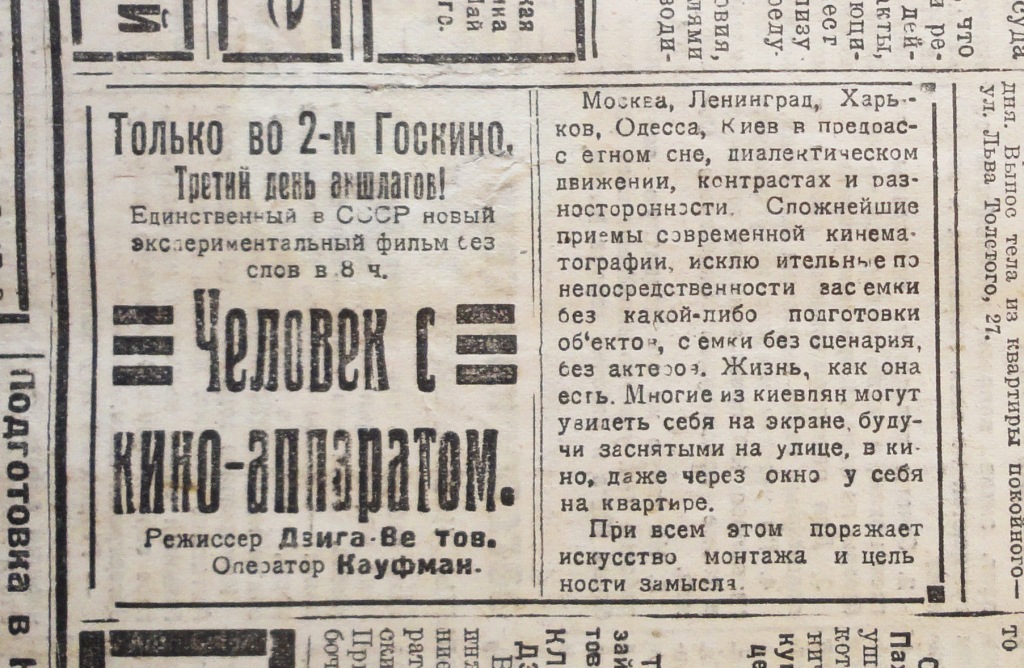

Культура й мистецтво

«Людина з кіно-апаратом»

Виробництво ВУФКУ 1928 року, автор-керівник – Дзига Вертов, голов. опер. М. Кауфман, асист. на монтажі Є. Свілова.

“Майстер іде вперед, а кайдани маніфестів тягнуться за ним.

Вертов, як і перше, говорить про життя, як його сприймає кіно-апарат. Він каже, що доданки цих сприйнять не міняють загальної суми. Але в мистецтві, а те, що робить Вертов, звичайно мистецтво, від переміни додаників сума цілком міняється. Отже ціла картина вже не життя, яким його бачить кіно-апарат, – це життя, що його створив монтаж Вертова та його групи.

Кайдани маніфестів тягнуться за майстром.

Вертов іде вперед.

«6-та частина світу» трималася на гіперболі написів, але самі держторгівські маштаби від полярного песця до виноградників говорили за себе. Ту саму гіперболу тітрів маємо й у «Одинадцятому». З погляду розгортання гіперболи «Одинадцятий» виявив себе, як провал, бо віддалення від Донбасу до Київа це не віддалення від Нової Землі до Криму. Шаленим монтажем Вертов хотів підмінити природній простір і зовсім не гіперболічну індустрію. Сталася невідповідність між бідністю й малими маштабами матеріялу та між темпом.

«Одинадцятий» міг би бути тільки, як частина «6-ої частини світу», але окремо він мав бути, бо без нього не було-б нової картини Вертова «Людина з кіно-апаратом». «Одинадцятий» з погляду монтажу був уже готуванням до нового надзвичайного вертівського фільму.

Говорити про мистецтво за-для мистецтва й про мистецтво тенденційне – це безглуздя. Великий майстер, працюючи над твором за-для мистецтва, створює шедевр великої громадської ваги. «Одинадцятому» куди до шедевру. Хоч тему мав і ювілейну, проте він дуже часто не підносився вище за монтажний орнамент, за-для монтажного орнаменту.

Те само могло трапитися й з новою вертовою картиною, коли-б у ній за головну дійову особу не була людина, оператор, Фігаро кінематографії, що прокидається вдосвіда й працює на повітрі, під водою й землею, що відбігає з рейок саме тоді, коли поїзд уже мав його розчавити, що повстав з-під ніг одеських рикш і із шклянки пива.

Цей оператор схоплює те життя людей і речей, яке ми бачимо, але не сприймаємо.

Дюамель в одному свому нарисі скаржиться, що люди, приходячи до шпиталю, дивуються з вилиску нікелю та білої фарби, але не бачать самої сути – страждання.

Гоголь, Достоєвський відкрили нам дух Санкт-Петербургу, Анатоль Франс – дух Парижу. Німецькі кінематографісти, що здіймали «Симфонію великого міста», чесно зареєстрували одну добу Берліну. Ми дізналися, що робить берлінець о 5-й, о 6-й, о 9-й год. ранку, о-півдня, після служби і о-півночі. Але дух Берліну був не розкритий. У Вертова немає певного міста й зовсім не важно, що «поштові скриньки» з київських вулиць монтують разом із Кузнецькнм мостом. Вертов не реєструє просто вияви міського життя, нещасні випадки, смерть, народження, спочинок, то-що. Але в своїй разючій грі темпами, то роблячи 5 хвнл. на хвилину, то висаджуючи час, вимикнувши життя, подає дух сучасного міста взагалі, міста не такого, як його бачить кіно-апарат, а своєрідного міста, що його викрили Вертов, його асистенти та оператор.

Вертов, підносячись над самим експериментом, подає своєрідну філософію міста.

Коли-б це місто було тільки місто, що його побачив кіно-апарат, то, звісно, не було-б великої різниці між «Парижем у-ві сні», «Симфонією великого міста» і містом із «Людини з кіно-апаратом». Хоч є зовнішні спільні моменти (велосипед у вітрині, поїзд і нещасний випадок із «Симфонії великого міста», і зупинка юрби в «Парижу у-ві сні»), проте ці три картини а-ні трохи неподібні.

Говоримо про це тільки для того, щоб Вертов не так уже цінував свої кайдани.

Сам Дзига Вертов називає свій фільм тільки експериментом. Можливо, це зайва скромність. «Людина з кіно-апаратом» майже виходить по-за межі лабораторних шукань. Це правдива картина, що хвилює не тільки свіжістю поглядів на матеріял, що хвилює не тільки своїми формальними досягненнями а й своєю тематичною глибиною.

Багато режисерів СРСР і за кордоном вихоплюватимуть з неї матеріял частинами, десятки і сотні молодих кіноробітників будуть з неї вчитися фотогенії, трактування натури, монтажу й операторського мистецтва.

ВУФКУ судилося дати світовій кінематографії новий шедевр. Хай же ВУФКУ використає його й забезпечить Вертову дальшу можливість так експериментувати.

Ці експерименти стануть гордістю української кінематографії.”

Н. У.

Proletarian Truth – 1928. – December 21.

CULTURE AND ART

“Man with a movie camera”

Production of VUFKU, 1928, author-supervisor – Dziga Vertov, head cameraman M. Kaufman, editing assistant E. Svilova.

“The master marches ahead, dragging along the shackles of his manifestos.

Vertov, as before, talks about life as it is perceived by the film camera. He says that the terms of these perceptions do not change the thing in its entirety. But in art, and what Vertov does is, of course, art, the change of terms completely changes the whole. So the whole picture is no longer life as the film camera sees it, – it is life created by the editing of Vertov and his group.

The shackles of the manifestos follow the master.

Vertov goes forward.

A Sixth Part of the World was based on the hyperbole in the intertitles, but the very scale of state trade from polar foxes to vineyards spoke for itself. We have the same hyperbolic intertitles in The Eleventh Year. From the point of view of the deployment of hyperbole, The Eleventh Year proved to be a failure, because the distance from Donbass to Kyiv is not the distance from Novaya Zemlia to the Crimea. Vertov wanted to replace natural space and absolutely not hyperbolic industry with crazy editing. There is a mismatch between the poverty and small scale of the material and the pace of the film.

The Eleventh Year could just have been a part of A Sixth Part of the World but it had to be separate, because without it there would not have been Vertov’s new picture, Man with a Movie Camera. In terms of editing The Eleventh Year was already a preparation for Vertov’s extraordinary new film.

Talking about art for art’s sake and tendentious art is nonsense. A great master, working on a work for art’s sake, has created a masterpiece of great civic importance. The Eleventh Year is far from a masterpiece. Although it had a jubilee theme, it often did not rise above montage ornament for the sake of montage ornament.

The same could have happened with Vertov’s new picture, were it not for the fact that the main character was a man, a cameraman, a Figaro of cinema, waking up before dawn and working in the air, under water and underground, running from the rails just when a train might have crushed him, rising from under the feet of Odesa rickshaws and from a glass of beer.

This cameraman captures the lives of people and things that we see but do not perceive.

In one of his essays, Duhamel complains that when people come to a hospital they are surprised by the shine of the nickel and white paint, but do not see the essence – suffering.

Gogol, Dostoevsky revealed to us the spirit of St. Petersburg, Anatole France – the spirit of Paris. The German filmmakers who filmed The Symphony of a Great City honestly recorded one day in Berlin. We learned what a Berliner does at 5 o’clock, at 6 o’clock, at 9 o’clock in the morning, at noon, after work and at midnight. But the spirit of Berlin was not revealed. Vertov does not have a specific city, and it does not matter at all that “mailboxes” from the streets of Kyiv are edited together with Kuznetskii Most Street in Moscow. Vertov does not simply register the events of city life, accidents, deaths, births, rest, etc. Rather, in his striking game with tempo, he either turns five minutes into one, or he ousts the sense of time, switching life off, giving the spirit of the modern city in general, a city not as seen by the film camera, but as revealed by Vertov, his assistants and cameraman.

Vertov, rising above the experiment itself, presents a kind of philosophy of the city.

If this city was just a city seen by a movie camera, then, of course, there would be no big difference between Paris qui dort, The Symphony of a Great City and the city in Man with a Movie Camera. Although there are external commonalities (a bicycle in a shop window, a train and an accident from the The Symphony of a Great City, and a crowd coming to a stop in Paris qui dort) these three pictures are totally different.

We are talking about this only so that Vertov will not value his shackles so highly.

Dziga Vertov himself calls his film only an experiment. Perhaps this is excessive modesty. Man with a Movie Camera almost goes beyond the scope of laboratory research. This is a truthful picture, which excites not only by the freshness of its view of the material, not only by its formal achievements but also by its thematic depth.

Many directors in the USSR and abroad will extract material from it in parts, and dozens and hundreds of young filmmakers will learn from it photogeny, interpretation of nature, editing and cinematographic art.

VUFKU is destined to give world cinema a new masterpiece. Let VUFKU use it to provide Vertov with a further opportunity to experiment in this way.

These experiments will become the pride of Ukrainian cinema.”

N. U.

I am very grateful to Julian Graffy, Emeritus Professor of Russian Literature and Cinema at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London, and Tom and Roksolyana Lasica for editing the translation of Mykola Ushakov’s remarkable review of the film.

MOSCOW

‘The Hero of the Film is the Camera’ (‘Lines of Resistance’, chap. 24, p. 339)

‘Kino’ #2, Moscow, 8th January 1929, page 3. E[zra] Vilensky

In an appreciative review, the day after the Kyiv premiere, Vilensky notes that the ‘film aroused heated debate in Kharkov and Kiev*. It is a long time since film production has delivered such sharp material. It is a long time since the Ukrainian public was so agitated’. He fears that ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ will suffer the fate of the majority of non-fiction films and insists that ‘we must not allow it to lie on a shelf until some unspecified time. The centre of the cinematic life of the USSR, Moscow, must see this film as quickly as possible’.

*This is presumably referring to the pre-release screenings and discussions recorded in the minutes dated 7th November 1928 in the RGALI Vertov archive, and noted in Professor MacKay’s paper at the beginning of the post.

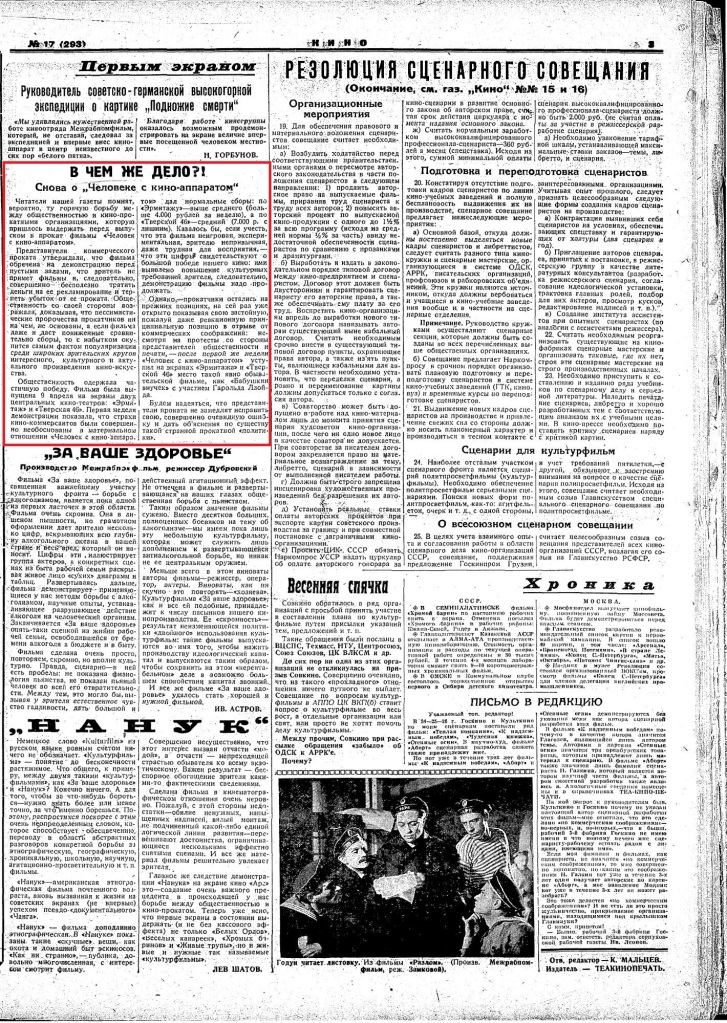

‘So What is the Matter?! Once again about Man with a Movie camera’ (‘Lines of Resistance’, chap. 25, p. 350).

‘Kino’ #17, Moscow, 23rd April 1929, page 3

The anonymous author repeats much of Konstantin Feldman’s comments in Vecherniaia Moskva asking readers to recall the ‘heated struggle between the public and the film exhibition organisers which had to take place before the release of “Man with a Movie Camera”….The public won a partial victory. On the 9th April the film began a run on the screens of two central cinemas, the Hermitage and 46 Tverskaia Street. The first week of the run showed that the fears of the cinema businessmen were completely unfounded. In material terms ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ did normal box-office: at the Hermitage it was higher than average (more than 4,000 roubles in a week), and at the Tverskaia it was average (over 7,000 roubles). If you bear in mind that this is a non-fiction, experimental film, which the viewer is not used to and may even find difficult to take in, then these figures would seem to provide evidence of a great victory for our cinema: they reveal the heightened cultural demands of our viewers, and in consequence the film should continue to be shown.’ However, the author complains that, despite this commercial success and protests from the public and press, ‘after a single week “Man with a Movie Camera” made way on the screens of the Hermitage and 46 Tverskaia Street for such an obviously philistine film as “Grandma’s Boy”, with Harold Lloyd.’

I would like to thank Professor Julian Graffy for providing the pages with the original articles.

GERMANY

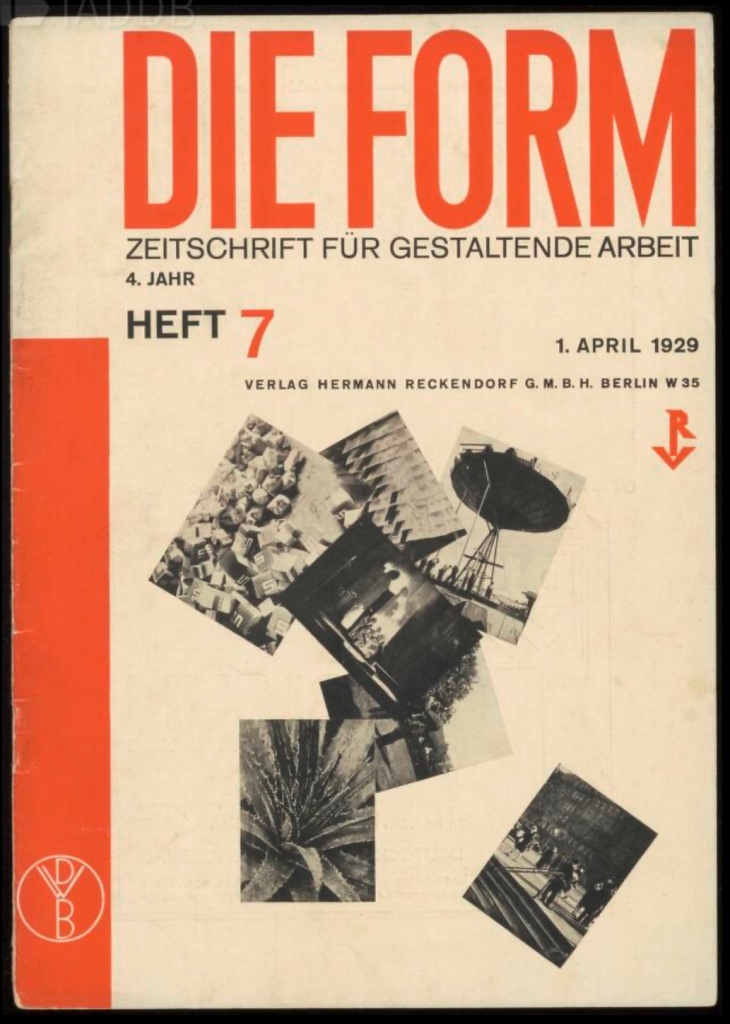

The 1st April 1929 edition of the influential design magazine Die Form, produced by the Deutscher Werkbund, included a preview of the Film und Foto exhibition featuring ‘Man with a Movie Camera’. Translation of the article below.

‘NEW RUSSIAN FILMS AT THE EXHIBITION

In Moscow a new film “Man with a Movie Camera” was recently previewed. The film, which takes simple everyday life by surprise and records it dynamically, was created by the young Russian film artist Dsiga Werthoff without actors, without any scenario and completely without intertitles. Hot, pulsating life, which seems to jump out at the viewer, is not only seen anew and given new forms by the film, it is experienced anew and is turned into a cinematic work of art without any literary or theatrical pathos. This is why this film can neither be told nor described in any way, it speaks its own language, which is derived from the possibilities of cinema. He shows us the facts – seen through the lens of the camera – from a different angle than we are used to seeing them.

The film made a strong impression on all viewers, who were composed of experts in the art of film and from literature, theatre and art circles.

Dsiga Werthoff’s film will also be presented to the public for discussion in Germany, for the first time, as part of the international Werkbund Exhibition “Film und Foto” in Stuttgart. As is well known, this exhibition aims to address all of the important issues of film and photography by showing demonstrations and lectures in order to encourage progress in these areas.

In addition to the new film by Werthoff, other previously unpublished films will also be premiered in Stuttgart. Individual directors and cinematographers intend to put together short instruction films especially for this exhibition, which should give an insight into their theories, working methods, and editing. Shorter published films by Pudowkin, Eisenstein, Schub and new cultural films from Russia will also be shown.’

Die Form, issue 7, 1st April 1929

Vertov’s friend, Sophie Küppers (-Lissitzky) wrote an article in praise of the film in the May 1929 edition of the influential art journal Das Kunstblatt, ‘Schaut das Leben durch das Kino Auge Dsiga Werthoffs’ (‘Look at Life through Dziga Vertov’s Kino-Eye’). In one of the most thoughtful reviews of ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ she gets right to the heart of the film: ‘..But life here is not only observed and fixed. It is experienced – formed deeply and chastely, and with a heart burning with poetry. Never before was womankind shown with such restraint, never before has the martyrdom of birth in art revealed itself as a drama of a few seconds. The whole range of human emotions is touched upon – quietly and with great dignity…Vertov’s optical tricks catch us unawares – if he has mystified us, so in the next moment he will laughingly explain his trick to us. Even as the wild chaos of the street is barely no longer whirring before us, he already shows us the assistant at her laborious editing work.‘

She concludes: ‘Vertov has received complete appreciation and enthusiastic acclaim from all progressive-minded people. His valiant co-workers loyally support him in his struggle for his work. A new language has truly been created, that cannot be imparted by any other communications medium other than the cinema apparatus. No written history, no verbal poetry, and no image will be able to give the following generations a truer testimony of the experience of life in our time than these film records of Dziga Vertov. Through his instrument he has rythmatized seeing; seeing resounds; the theatre broke into pieces – what we experience through him is only – REALITY.‘

[Excerpt from ‘Lines of Resistance’, chap. 26, pp. 359-360. Translation by Oliver Gayken]

The following Berlin newspaper extracts are difficult to read so there is a link to each article via the newspaper title under each review.

A review in the 12th June edition of Berliner Volks-Zeitung of a ‘poorly attended’ lecture about ‘Kino-Eye’ given by Dziga Vertov on the 9th to the National Association of Film Art in the Phoebus Theatre, Berlin. The reviewer (Franze Schnitzer – see below) wrote that the lecture was too technical for the audience and best suited to ‘experts in a cameraman’s club’. He thought that ‘what some samples from Werthow’s montage showed was, in a certain sense, a refined Ruttmann film. “Symphony of a Great City” only depicted the outward appearance of the big city, the Russians, as always, take convincing and politically oriented pictures, and also depict something like the people’s soul. Werthow is a fanatical fan of the candid film. One of these, “The Man with the Movie Camera”, will soon be showing in Berlin.’

The day after the premiere a small notification of the film’s release by Derussa* appeared in the 3rd July edition of Berliner Volks-Zeitung.

*The German-Russian Film Alliance

‘The first full-length, complete film by the Russian film art association “Kino-Eye” is now being released by Derussa. Direction and Montage: Werthoff’.

A review in the Berlin Communist newspaper ‘Die Rote Fahne’ (The Red Flag) on Friday 5th July. Difficult to read even in the original because of the ‘Faktur’ black type, it concludes that the film is ‘very interesting artistically, with masterful montage and camerawork, but overflowing with details and without a continuous rythm. Ruttmann’s film “Symphony of a Great City” is more economical than this Werthoff film. Werthoff’s path with “The Man with the Camera” deviates from the real tasks of Russian “Cinema Eyes”.’

A review of ‘Der Mann mit der Kamera’ in the Saturday 6th July edition of Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung (unfortunately difficult to read even in the original as it is typeset in Fraktur black letter script). DAZ was one of the principal German newspapers.

A mixed review that rather misses the point of the film in the 10th July edition of Berliner Volks-Zeitung (translation below). The misplaced photograph of the star of ‘Sweet and Sinful’ illustrating the piece would have also irritated Dziga Vertov I imagine!

The Man with the Camera

In the Marmorhaus

‘Wertoff’s film culture and the goals of the Russian film group Kino Eye have already been discussed by this writer a few weeks ago1. At that time one had only seen excerpts from the “Man with the Movie Camera”, a documentary and a film with no intertitles that resembles Ruttmann’s “Symphony of a City”. There is no actual content to be seen here. The eye of the spectator experiences a city and its inhabitants, people who work, play sports, join committees, have children, mourn their dead, get divorced, work again, rush through the city, and have their fun and their sorrows. The man with the camera is everywhere. At the wedding, at the divorce, when having children, in the cemetery, when there is a fire and everywhere and all the time. He turns, turns, turns. He records the reality and then goes into the editing room and glues together a wonderful song out of it. The hymn of a city, Werthoff’s pictorial song, begins with an andante and ends with a magnificent furioso, which is brilliantly assembled, but which will not be of interest to a non-literary audience or a viewer unfamiliar with the French absolutists and the birth of the avant-garde.

The film runs without intertitles. For the German provinces and for the many smaller cinemas (even in Berlin) this is a catastrophe. In the Marmorhaus the excellent accompaniment music by Schmidt-Boelke2 [sic] was played now and then to the audience so that the various scenes could be distinguished and understood. But in a smaller cinema with only a gramophone or an organ or a man with a violin – what will the audience do?

Werthoff’s picture is a treat for film professionals. All weekly newsreel cameramen should watch it. You can learn from him. But the film is too long. You can’t watch the weekly news for two hours3. What is very nice, however, is that Werthoff understands how to explain film as a craft over and over again, in close relation to the following scene. Rather like a table of contents. You can see a film editor arranging and sticking different film strips together, spooling and rolling them.

It is all very beautiful, and it should be acknowledged that this film is worth seeing and a great artistic achievement, despite some foolish antics. But …. what will the audience outside of the area around the Memorial Church4 have to say about this series of pictures? It is a muddle, from the tram to the railway, from work in the factory to people on the street. The housewives are tired of worrying about their children, of doing housework, and of the whole week. And now you sit in “your cinema” and see nothing but the tram, factory work, housework, children and all the excruciating hustle and bustle of everyday life. In addition, an untrained eye may not be able to cope with the terrific rhythm of the sequence of images. Also about the film see the last paragraph of the article on this page “Cinema of the Workshop”‘. F.S. (Franze Schnitzer)

Paragraph referred to:

‘Every now and then, however, a local theatre owner sets his ambition aside and plays one of those much-praised films often referred to as “art films”. For example, a now much-celebrated Russian film. And what does he have to listen to from his very candid audience? “Man, it looks as though I’m looking at the Kurfürstendamm through your bandy legs!”*’ Franze Schnitzer.

*An odd phrase in Berlin dialect.

1See above for Schnitzer’s 12th June review of Dziga Vertov’s Berlin talk (this may have been one of the articles that Dziga Vertov was complaining about below, although it only mentions Ruttmann).

2Werner Schmidt-Boelcke (1903-1985) was a German conductor and composer of film music.

3An exaggeration. The film is around 1 hour and six minutes long, similar to Ruttmann’s film.

4The Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church is at one end of the Kurfürstendamm.

Dziga Vertov complained in a long letter to the Frankfurter Zeitung (written from Berlin on the 8th July, but not to a Berlin newspaper for some reason) that ‘one segment of the Berlin press’ had made the accusation that ‘…Kino Eye essentially represents a “fanatical” continuation of the principles and practices carried on by a certain Blum (in the film “In the Shadow of the Machine”)1 and Ruttmann (Berlin, “Symphony of a Big City”), both of whom are unknown to me’. Albrecht Blum had lifted parts of ‘The Eleventh Year’ for his 1928 film2, and Walter Ruttmann did acknowledge the influence of Vertov’s theories. There is a long, generally favourable review by Siegfried Kracauer in the Frankfurter Zeitung of 19th May3 so perhaps Vertov thought he would find a readership sympathetic to his letter in this newspaper. Most reviews of the film in the Berlin press were positive (many making reasonable comparisons with Ruttmann’s film) but he could have taken offence at a very critical one in the 3rd July issue of ‘Kinematograph’ which concluded that ‘Vertov had nothing new to offer and could no longer surprise the audience, since Ruttmann and others had already used the same techniques’.

Letter excerpt from ‘The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum’, p. 221.

1The reference to Blum was removed from the published letter [‘Lines of Resistance’, chap. 28, fn. 16].

2 ‘The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum’, p. 221

Vertov also explained his film and complained about Blum in an interview included in ‘Lines of Resistance’ [chap. 26, pp. 366-367].

Chapter 28 in ‘Lines of Resistance’ has more on ‘Vertov versus Blum’. Chapter 29 has more on Vertov and Ruttmann.

3‘Lines of Resistance’, chap. 26, pp. 355-359.

NOTES

[1] An article in ‘Proletars’ka Pravda’ on the 12th January 1929 entitled ‘Gravediggers from VUFKU’ by Mykola Yatko (1903-1968) who was a screenwriter and journalist, and had worked for VUFKU in Kyiv and the Odesa Film Studio. His article was sharply critical of VUFKU’s distribution policy that he thought favoured ‘box office hits’ at the expense of real works of art. He cites the poor advertising of the current screening of ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ in Kyiv as an example. Looking at the paltry announcements for the film in the newspapers he had a point.

‘…Преса кричить про «Арсенал», а прокатники тільки всього виставили в 1-му кіні скромну дошку з світлинами «Арсеналу», а праворуч од неї пишний плакат «Мулен-Ружд» з голими ніжками танцюристок. «Людину з кіно-апаратом» без жодної об’яви (принаймні в Київі), без

жодного плакату пускають без підготовки в другорядному кіні…Наша й московська преса присвятила докладні статті «Людині з кіно-апаратом», громадський перегляд одностайно привітав ВУФКУ з новим досягненням, вирішено було всіляко сприяти й популяризувати в

масах «Людину з кіно-апаратом», а прокат просто всупереч логіці просто свідомо закопує кращий радянський фільм…’

‘…The press is shouting about “Arsenal”, but the distributors only put up a modest board with photos of “Arsenal” in the First Cinema1, but to the right of it is a magnificent poster of “Moulin Rouge” with the bare legs of dancers. “Man with a Movie Camera” is allowed to go ahead without any advertisement (at least in Kyiv), without any poster, and without any preparation in a second-rank cinema…Our and the Moscow press devoted detailed articles to “Man with a Movie Camera”, the public review2 unanimously congratulated VUFKU on the new achievement, and it was decided to promote and popularise “Man with the Movie Camera” among the masses, but the exhibitors, contrary to logic, simply deliberately buried the best Soviet film…’

1Goskino No. 1

2Julian Graffy suggests this could also mean ‘public reception’. Perhaps this is referring to another pre-release December screening at the VUFKU studios to which the public were invited, or the same one that Mykola Ushakov attended? The Dovzhenko Centre has no information about this.

[2] Mykhailo Kalnytsky suggests that ‘N.U.’ is the renowned Kyiv poet and cultural figure Mykola Mykolayovich Ushakov (1899-1973) who sometimes used these initials (for the Russian version of his name, Nikolai Ushakov). Professor Yuri Tsivian has read the review and says that it is clearly by Ushakov as it is similar in style to his book ‘Tri Operaturi’ (‘Three Cinematographers’, 1930).

Fair Use claimed for any copyright material as it is copied solely for research purposes and commentary only, without financial gain. Attribution and links given where known. Contemporary Soviet photographs are generally in the public domain.

I have added links to other websites and information to enhance the value of this post and although I have taken reasonable steps to ensure that they are reputable, I am unable to accept responsibility for any viruses and malware arising from these links.

The screenshots are from a version of the film posted on YouTube by a Ukrainian source AVG which is no longer available. The screenshot times [hr:min:sec] are from the Lobster Films/Eye Institute 2014 restoration of the film.

Pravda announcements extracted from the East West Pravda Digital Archive.

Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung and Berliner Film-Zeitung newspaper announcements and reviews extracted from the ZEFYS digital archive of the Berlin State Library.

‘Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties’, edited by Yuri Tsivian with translations by Julian Graffy and research by Aleksandr Deriabin, published by Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2004.

‘The Vertov Collection at the Austrian Film Museum’, ed. Thomas Tode & Barbara Wurm, SYNEMA, 2006. There is online access to the collection, which includes many more newspaper articles and announcements.

For information on the shooting schedule and details of the film locations see my blog post Man with a Movie Camera: the film locations.

Please contact me on opinionated.designer@gmail.com with any comments and corrections.

Richard Bossons, Oxford, September 2020.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (not mentioned above)

I would like to thank the following for their invaluable help and information, and patience in answering many questions. Inclusion does not imply endorsement of anything in this blog post. Any errors and omissions are entirely mine.

I am indebted to my collaborator in Kyiv, the renowned historian of the city, Mykhailo Kalnytsky, for finding the Kyiv and Kharkiv announcements, the first review of the film, and the Mykola Yatko article. The photograph of the Goskino No. 2 Cinema is also from Mr Kalnytsky.

Professor Julian Graffy, for his invaluable comments, corrections, and information, and for his contributions also acknowledged in the text.

Anna Onufriienko, Senior Curator and Research Scholar at the Oleksandr Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv, for providing the extracts from the VUFKU minutes, the Ukrainian poster, and other vital information.

VUFKU minutes from ‘Minutes of the VUFKU Board (1922-1930)’, compiled by Roman Roslyak, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, the Rylsky Institute of Art Studies, Folklore & Ethnology, Kyiv. Lyra-K Publishing House, 2017.

Alyna Fedorovich, Chief Curator, Museum of Moscow, for information on the Hermitage Theatre.

Konstantin Dubin, Head of Department, Kharkiv Historical Museum, for information and photographs of the K. Liebnecht Cinema in the city.

Ukrainian and Russian translations, not otherwise credited, by Tatiana Kovaleva.

German translations by me and TextMaster.

FOR AN UPDATED VERSION OF THIS POST PLEASE GO TO: richardbossons.academia.edu/research

ALL ORIGINAL CONTENT COPYRIGHT © Richard Bossons 2020

Kінець

End.